Introduction

India is constitutionally a secular country, but polarizing aspects of its religious culture and ethnic diversity have undermined electoral politics at an alarming speed and in an alarming manner.

Dr. Ambedkar, the author of India’s constitution, and Mahatma Gandhi (and even Jiddu Krishnamurti) tried to prevent that development in their own diverse ways.

Ambedkar tried by promoting the secular values of freedom, equality and fraternity with pragmatic arguments; Gandhi tried it with his inclusivity, especially by promoting good relations between Hindus and Muslims; and Krishnamurti contributed by radically questioning the violence-prone mechanisms of identity formation around the ‘me’.

What specific advise they would give contemporary Indians could be a worthy exercise in educated guessing, but they would certainly observe the current drift towards religion-based authoritarianism with consternation.

Education

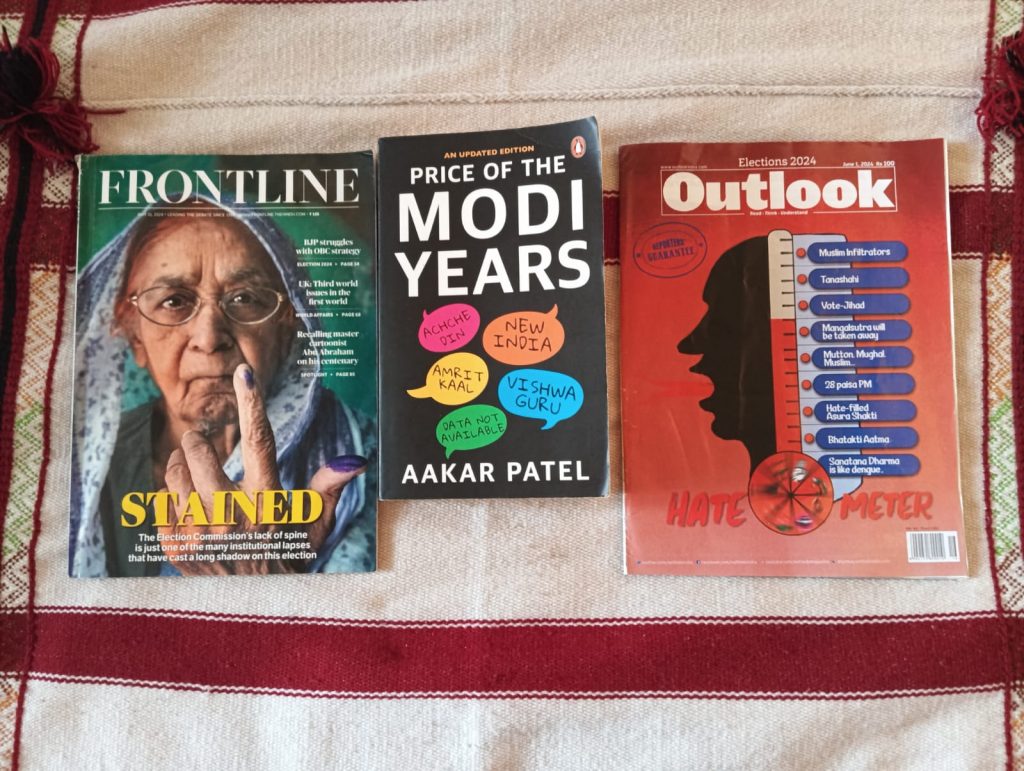

My own political education about India’s current affairs I’m receiving from, among others, the below pictured publications, which do not paint a pretty picture.

While reading the venerable Frontline and Outlook magazines during the election, and specifically Amnesty International India Aakar Patel‘s Price of the Modi Years, I became really worried about Indian politics.

While reading the venerable Frontline and Outlook magazines during the election, and specifically Amnesty International India Aakar Patel‘s Price of the Modi Years, I became really worried about Indian politics.

Patel’s book opens with a devastating list of 50 international indices and ratings indicating that since 2014 India was slipping on almost all metrics, except some economic ones like competitiveness and innovation.

India fell in ranking in the spheres of democracy, human development, civil liberties, rule of law, press freedom, religious freedom, air quality, sustainability, the gender gap, intellectual property, food security and then some. Instead of reflection and realistic analysis, the response of the government in 2020 was a media campaign to correct perceptions, and some proposing India create its own indices. Patel concluded that,

The record leaves little room for debate or dispute. The scale and rapidity of decline in governance after 2014 is manifest. India was struggling to keep up with the world and sinking on several fronts. It may appear strange that anyone should have thought that reversing this performance required ‘a massive publicity campaign’ which would ‘shape India’s perception’ through advertising and more websites, but that is what Modi thought and how he oriented his government to act [p. 33].

Then page after page, going on for 450 in total, Patel’s “report card on India” relentlessly exposed many of the failed policies, illegal tricks and unconstitutional schemes by Modi and the BJP, apparently condoned by a partisan supreme court, largely under-reported by a suppliant press, uncritically accepted by their followers, and impotently decried by the opposition.

The Election

But now I’m somewhat relieved with the outcome of the election (fortunately accepted by all as fair), which was reported as “India Cuts Modi Down“, illustrated by the following facts. BJP lost its seat in the district where the highly controversial Ayodhya temple was recently inaugurated–a feat high on its wish list–accompanied by lots of pomp with Modi as the guest of honor, or better, the officiating, non-official high priest.

Then BJP got halved in the conservative states of Uttar Pradesh, Maharashtra and Haryana, all part of BJP’s heartland, but also important agrarian states. Two states went from 100% BJP or BJP-allied representation to 100% Indian National Congress (INC), i.e. one seat from Nagaland and both seats from conflict-ridden Manipur (which means that the INC should move quickly to negotiate reconciliation and normalization).

All in all BJP lost 63 seats, while they had hyped the projection that their coalition could get a whopping 400+ out of 543 total seats in the Lokh Sabha, India’s chamber of representatives. Maybe they hoped for the magic realization of a self-fulfilling prophecy with the help of some of their favorite deities.

What motivated the Voters?

But this also scared voters, especially minorities (of which 200m Muslims), about what protections and privileges Modi and the BJP could take away from them with a super-majority, for example with a rewritten constitution (there are some versions floating around taking away all voting rights from religious minorities).

Another section of the population it might have lost are the farmers, whose plight has not improved since Modi promised to double their income in 2014, and who felt existentially threatened by a couple of agrarian reform bills against which they vehemently protested with success.

Then Modi’s mismanagement of the COVID pandemic, especially during the second wave in the spring of 2021, might also have cost him votes, certainly from the underpaid frontline health workers, and families and friends of the poor who didn’t get oxygen nor vaccines in time. And then those working in the deliberately shackled NPO sector (with 19m people involved) would have lost reason to vote for Modi, as would be the case for producers and consumers in the demoted journalism business.

Anyway, Modi, who now speculates that his birth was maybe not biological, has to step down from his self-promoted, Priest-King status to become an ordinary politician doing ordinary coalition politics with his secular allies to form a government and take his third term as India’s prime minister.

He claims he was humbled by the election outcome, but his spokesperson stated that “the way the government was run for the last 10 years, it will be the same”, which after reading Patel, doesn’t sound reassuring.

Not Just India

And I do not want to merely single out India on its right-ward, theocratic slide. There is a global tendency towards authoritarianism in which religious fundamentalism plays a huge role.

I have seen this happening up close in the USA and even a highly developed, progressive and tolerant country like The Netherlands can, and just did, fall into xenophobia by voting a far right-wing party, led by an Islamophobic politician, into power as its largest party. Fortunately such set-backs are only temporary and India might still set a great example in that regard.

I’m comfortable with debating conservatives justifying classical liberalism and the value of communal life, but we should by all means abide by a Habermas-inspired, dialogue-based, negotiated, mutual accommodation leading to peaceful co-existence. Maybe we should appeal to the religious idea of the sacredness of the stranger as guest, and / or the philosophical idea of deep reference for the Other.

The demonizing of Muslims, Dalits, Palestinians, Israelis, colored immigrants, and whoever else you don’t like based on fanatic ideologies, fundamentalist theologies or unacknowledged racism should be challenged, which is not always easy as it feels often like poking a bear.