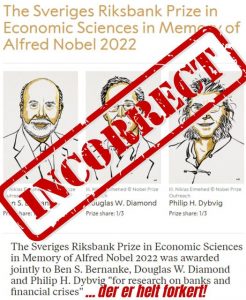

It is an honor to be awarded the prestigious Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences. This year it went to three American economists “for their research on banks and financial crises”. The lucky recipients were Ben S. Bernanke, Douglas W. Diamond, and Philip H. Dybvig and the Swedish committee titled their justification “Financial Intermediation and the Economy”.

For reasons to be shared here, this award is also an unexpected gift to the international monetary reform movement. Not because the Nobel committee or its award recipients are siding with this movement and its analysis of money and banking, but because the award is given for research which is based on the outdated, refuted, incorrect, mistaken ‘intermediation theory of money and banking’ based on the idea that banks are the intermediaries between savers and borrowers.

Meanwhile the truth, ladies and gentlemen, is that loans create deposits, because, when a loan is originated the borrower receives money which had not been in existence before. The commercial bank just credited his or her account and received in exchange the signed loan contract of the same value. This theory is named the credit creation theory, because a credit is created out of nothing, which then can be spend into the economy where it is received as good as money, no questions asked.

This is counter-intuitive, for sure, but we will see that even the research staff in the Swedish Riksbank, which is involved in awarding the prize, knows that the credit creation theory is the correct one and not the intermediation theory. I am sure you see the reason of the Ig Noble prize looming.

The news of this award came to me from someone sharing an article by Scott Horsely of the US-based National Public Radio (NPR), and Horsely, as so many reporters merely passing on official statements, dutifully reproduced the idea that,

Banks help to foster a more productive economy by channeling excess cash from depositors to borrowers in need of money to build homes and factories and businesses.[1]

So, he is, innocently or not, parroting the Swedish academy, which stated along the same lines that,

Financial intermediaries such as traditional banks and other bank-like institutions facilitate loans between lenders and borrowers, and thereby play a key role for the allocation of capital.[2]

A little further in the justification they state that,

. . . it would likely be prohibitively costly for a home buyer to write a separate financial contract with every individual lender that ultimately finances her mortgage. Furthermore, if every lender required the contract to stipulate that she had the right to get her money back on demand, costs would escalate quickly, as the borrower may repeatedly have to seek refinancing.

To solve this problem, financial intermediaries such as banks and mutual funds exist. These institutions channel funds from savers to investors, receiving funds from some customers and using the funds to finance others.

Of course people in the monetary reform (MR) movement immediately perceive the problem here, i.e. the committee still believes in the refuted intermediation theory, which has been replaced by the correct credit creation theory.

The irony is that researchers working at the ‘Monetary Policy Department and the Payments Department of the Riksbank’ of Sweden know where money comes from. I am not going to paraphrase but let them tell us themselves:

Commercial bank money is created when banks give loans

To understand what commercial bank money is and how it is created, we can look at an example that starts with a customer wanting a loan. The loan involves the customer signing a promissory note, that is, a promise to pay back the loan in the future as a certain amount of money to the bank. In return, the bank deposits a sum of money into the customer’s account with the bank.[3]

The source they refer to in ftn. #3 is the now quite famous 2014 paper by McLeay et all.[4]

3. For an accessible primer for how banks create credit, see McLeay et al. (2014).[3]

And this is not the only paper to be found at the Riksbank web site incorporating the credit creation theory of money. Another paper addressing CBDC even explicitly takes it as its starting point.

The paper builds on a model of bank loan supply that is based on the actual practice of banking. In the model, banks can create potentially unlimited amounts of loans and deposits in their own books. When banks give out loans and create deposits, they must also make sure that they can satisfy customers’ outflows to other banks, cash or CBDC. To satisfy these outflows, banks need central bank reserves.[5]

Given the above analysis it is my conviction that this is a gift for the monetary reform movement, because it can hammer home its message, citing chapter and verse, that 1) modern, mainstream macroeconomics (except for the Post-Keynesian theory of endogenous money [6]) is mistaken in its monetary theories; 2) that monetary reformers have the right theory; and 3) that radical monetary reforms are required and possible based on that theory.

These reforms could be boiled down to:

1. All official money – be it cash, money-on-account or new forms of digital currency – is created by a monetary state authority, according to the needs of the economy in a transparent and accountable process.

2. Money is created free of debt, and is directly spent into the economy via the state by way of government expenditure or directly distributed to the citizens as an equal dividend.

3. Private banks cannot create official money as credit. They only act as payment service providers and/or financial intermediaries by lending and investing existing official money, which they obtain from savers and investors.[7]

Furthermore, this committee of the Swedish academy and Swedish central bank should be nominated for next years Ig Noble Prize for improbable research (I used their logo above), because they gave it to research based on an imaginary, outmoded understanding of banking.

Following the motto of the Ig Noble Prize of “Research that makes people LAUGH . . . then THINK”, we can honestly say the 2022 economics award makes us laugh for its flat-earth-like outdatedness, and makes us think about why on our round earth the committee would give the prize to these economists.

And there is a precedent for giving allegedly successful entities that prize, like in the 2002 Ig Nobel prize for economics given to many accounting and financial entities “for adapting the mathematical concept of imaginary numbers for use in the business world” leading to financial crises and accounting scandals.[8]

So, what to do with this? Can we protest the prize? Instead of joking about the Ig Noble prize, look at its nomination procedures?[9] For truth’s sake maybe we should.

P.S.: Next door to Sweden in Denmark the monetary reform organization Gode Penge is not too happy with this prize either. On Facebook they gave the same explanation accompanied with a clear image.

Sources

[1]. Horsely, Scott. 2022. “Ben Bernanke among 3 American winners of Nobel Prize in economics”. NPR, 10 Oct 2022.

[2]. The Committee for the Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel. 2022. “Financial Intermediation and the Economy”. Scientific Background on the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel 2022. The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, 10 Oct 2022.

[3]. Armelius, Hanna & Carl Andreas Claussen, David Vestin. 2020. “Money and monetary policy in times of crisis”. Monetary Policy Department and the Payments Department of the Riksbank. Riksbank of Sweden. Economic Commentaries, 4 (11 June 2020): 1-15.

[4]. McLeay, Michael & Radia, Amar & Thomas, Ryland. 2014a. “Money Creation in the Modern Economy”.Monetary Analysis Directorate. Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin (Q1, 2014): 14-27.

McLeay, Michael & Radia, Amar & Thomas, Ryland. 2014b. “Money in the modern economy: An introduction”. Monetary Analysis Directorate. Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin (Q1 2014): 4-13.

[5]. Juks, Reimo. 2020. “Central bank digital currencies, supply of bank loans and liquidity provision by central banks.” Sveriges Riksbank Economic Review, 2 (2020): 62-79.

[6]. See for example: Rochon, L.- P. and S. Rossi. 2013. “Endogenous money: the evolutionary versus revolutionary views”. Review of Keynesian Economics, 1 /4: 210–29.

[7]. International Movement for Monetary Reform. 2018. “About the IMMR & Our Manifesto”. IMMR web site.

[8]. Ig Nobel Prize Winners 2002.

[9]. The Ig Noble Nominations. “How to Nominate Someone”. Improbable Research web site.