CONTENTS [Article in pdf]

Introduction

Context of Discovery

Analysis I: The Sympathetic Theosophical View

Analysis II: The Critical Theosophical View

The Sympathetic and Critical Views Interpreting Each Other

First strategy

Second Strategy

Specific Questions and Answers

What was K’s experience of Benediction?

Was K enlightened or not?

What is true and what is false in K’s teachings?

Was K living his own teachings?

Postscript

Bibliography

Endnotes

INTRODUCTION

This article focuses on a few aspects of the Theosophy-Krishnamurti nexus and probably will only be of interest for those who like to think through the relationship between the very successful New Age movement of Theosophy and one of the most intriguing persons coming out of that movement, the Indian spiritual philosopher Jiddu Krishnamurti (from here on named K).

The article is based on an exchange of e-mails between a then anonymous writer and myself in November 2005, which I later posted as “Krishnamurti Discussion“. Because we both expressed an ambiguous relationship to K and his teachings, the exchange became a vessel to explore these in depth. What I added are some more autobiographical and narative elements inspired by my recent engagement with narrative identity theory and I expanded some arguments for the sake of clarity. I am also leaving intact some very stark statements I made about K with which I do not agree anymore, but were justified within the framework they were made.

Before diving into the intricacies of the exchange, a little introduction to the larger framework which this discussion took into account might be helpful.

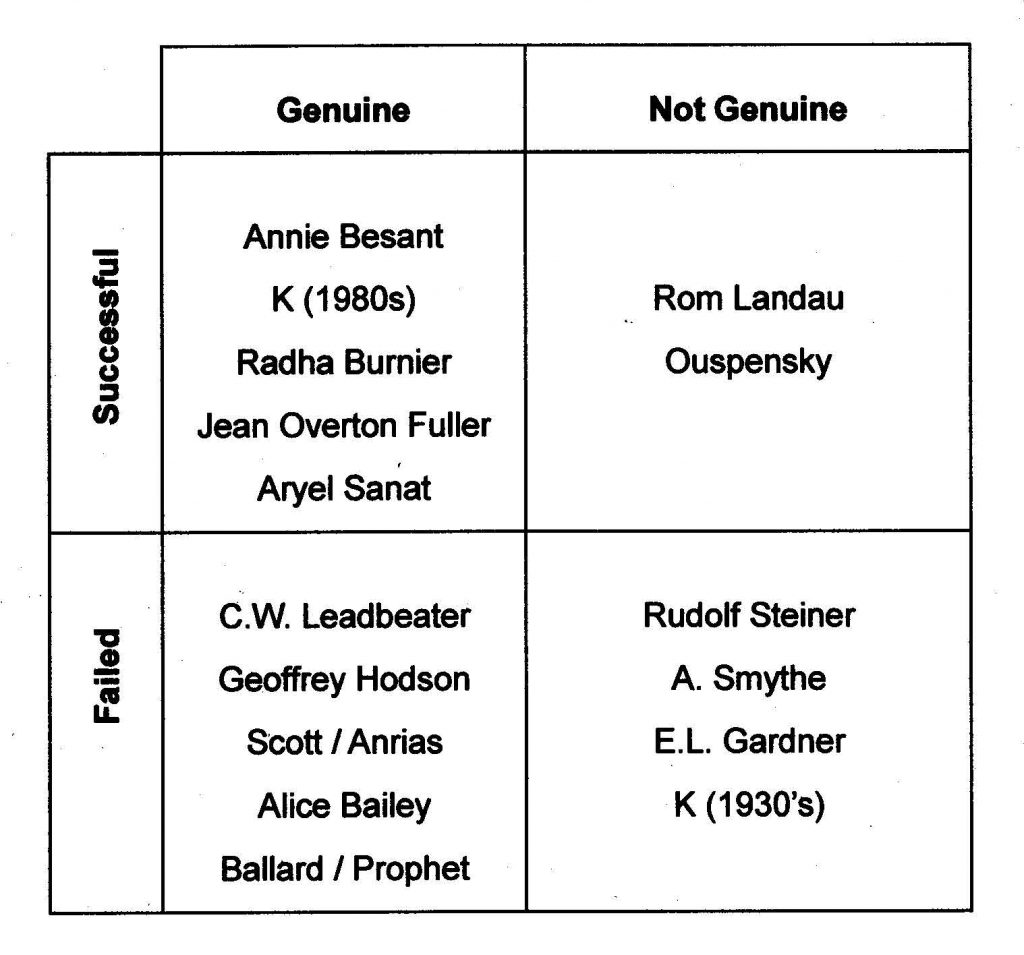

Little did I know that, when I made a clarifying matrix of possible Theosophical perceptions of Krishnamurti’s metaphysical status, that the contradictory position I included in that matrix, i.e. the Project was Not Genuine & Successful, would develop into the one I now find most likely.i

The logic of this matrix was based on the possible combinations to the answer to two questions: Was the World Teacher Project with Krishnamurti perceived as genuine? And was it perceived as successful? The Project, as I will call it from here on, was the expectation of, and preparation for, the return of a great teacher in the form of the Christ overshadowing again a chosen vehicle like he had done with Jesus of Nazareth, but now through the young boy Jiddu Krishnamurti. With ‘genuine’ was meant that the initiative of the Project lay in some transcendental source of supreme intelligence and with ‘successful’ was meant whether the original intention of the transcendental source of intelligence had come to fruition.

The possible answers to these two questions generated the four following positions:

1) The project was perceived as genuine and successful;

2) The project was perceived as genuine, but failed;

3) The project was perceived as not genuine and failed (of course); and

4) The project was perceived as not genuine, but succeeded!

And for all the four possible positions there were Theosophists or allied thinkers taking the different positions. The most important among them I discussed in a previous paper, but here they are placed in their proper quadrant:

The contradictory position is the Not Genuine & Successful one, which was thought to be plausible by the polish-British author Rom Landau and the Russian esotericist Pyotr Ouspensky, whose views Landau reported on. Their reasoning was that the Theosophical leaders Annie Besant and Charles Leadbeater just experimented with a sensitive boy to make him believe he could become the next great Christ-like teacher and that–low and behold!–the experiment produced a spiritual teacher of very great charisma and high caliber. Therefore the project was not genuine, but still successful.

When I did this research I was convinced of a quite different position. I thought that the Masters, i.e. a group of allegedly superhuman beings working in the deep background, had really directed the Theosophical luminaries Blavatsky, Besant and Leadbeater to prepare the way for a new Avatar, but that K was not up to the task and exited the Project. This was not as most Theosophists had expected. Though Leadbeater was initially sympathetic to K’s claims of transformation, in the end he didn’t buy it, while Besant went along with the idea that K was being overshadowed and then tried to harmonize the different factions developing in the Theosophical Society. My perspective was that K had indeed abrogated the Project, though very quickly turned around and claimed its success after all, but then on his own terms. In this interpretation the Masters moved on and expressed through some of their other trained channels their view of what had gone wrong. I gathered and combined these critical views in two pamphlets, which were released alongside the paper.ii

At the end of both pamphlets I made the case, with the help of the British philosopher of history Arnold Toynbee, that, as flawed K’s teachings might be, the combined impact of his charisma, life history and teachings would result in the foreseeable future in a new, though still flawed, civilization replacing the current globalized western one, provided the western one would not arrive at a level of sustainable maturity with the help of esoteric sources.

A few years later I was approached in an e-mail by someone who posed some really profound questions about K’s life and the many possible interpretations circling about him. This inspired me then to develop as well as possible, but still in a reasonably short response, the two dominant positions regarding K: The Genuine & Successful one and the Genuine & Unsuccessful one. What follows is an expanded version of this e-mail.iii

Context of Discovery

I shared with my correspondent that I also had a very ambivalent relation to K and his teachings and that, because K had such a profound influence on my life and thinking, I had been pursuing many of the questions my correspondent did.

When I first started dabbling in K it became quite clear that he had something very transformational to say, meaning that, while or after reading him, I would find myself with changed and awakened states of alertness about my surroundings and the workings of my own mind, though not actually knowing how or why. After a while I got the ‘hang’ of his teachings and started experimenting increasingly on my own during long walks and discussions with others.

Just after reading his remarkable biography in the spring of 1980 by Mary Lutyens, Krishnamurti: The Years of Awakening, I realized he was still alive. I hitchhiked to Saanen, Switzerland that summer and participated in the gatherings for two weeks. Just before hitting the road I had started reading Krishnamurti’s Notebook and, after a while at my Swiss destination, I was having similar experiences of benediction and bliss as described by K. These experiences only lasted, on and off, for the time I was in Switzerland.iv

I also found a little autobiography there, in French, by K’s former friend Vimala Thakar titled On an Eternal Voyage. From reading the account of her experiences with K and her own enlightenment, I derived the conviction that what K inspires us to do would indeed be feasible.

After many years of being a ‘purist’ Krishnamurtian, I developed again an interest in Theosophy, to which I had been previously exposed during high school. With all the ‘occult’ phenomena surrounding K it seemed to be a feasible project to harmonize the two outlooks. This did not have a high priority though. I was more interested then in philosophy, east and west, and especially found phenomenology, philosophy of science and Advaita Vedanta to my taste.

A sudden change in my philosophical endeavors happened when I found an early work by Sartre on ego-genesis titled The Transcendence of the Ego, which, because it came very close to what K was saying, provided a bridge and framework to re-interpret K in existential-phenomenological terms, an endeavor undertaken by many others I later discovered. The basic idea is that consciousness is originally ego-less, it has no self, but, because consciousness operates in a specious or thick now, it has the ‘space’ to reflect back on itself and catch its own ‘just past’. Sartre makes the case that in this self-reflexive move the ego arises as the product of the restructuring which happens in acts of self-awareness. The ego arising from this reflection is then seen as the carrier of all kinds of attitudes and dispositions. For example, when I meet the same person a couple of times and experience the meeting as pleasant, I might upon reflection conclude that I like this person thereby transferring the ephemeral quality of the encounter to my ‘self’ as its carrier and be able to say “I like this person”. At the same time the quality can also be transferred to the other person and conclude that that person is likeable as if it were a continuous attribute. This transformation is in itself quite innocent and maybe even helpful in finding one’s bearing in social life (‘life might be nicer if you are more likable and find more likeable people’), but Sartre’s point is that the ego and its imputed qualities is a derivative phenomenon, it is a construct. In a more simple form both Nietzsche and K said something similar: a thinker does not precede thought; it is thought which creates the thinker.

Anyway, this encounter with Sartre pretty much strengthened my conviction that phenomenology was not only fruitful for my understanding of both K and myself, but also of religion and mysticism in general to the point that I wrote an article making the case that Theosophy and phenomenology should as far as possible appropriate each other.v Later I found phenomenology very helpful in understanding conceptual art, especially the French pioneer in this genre Marcel Duchampvi, and it was my load-stone in the investigation of ‘narrative identity theory’ as the best tool to understand this most plausible of identity theories.vii

Another breakthrough in the mid-1980s, again quite unexpected and of a very different kind, was when I found Cyrill Scott’s The Initiate in the Dark Cycle.viii That book hit hard and deep. I was open to the profound Theosophical critique of K laid out in that book because I had started to doubt the feasibility of K’s transformation and had become disappointed trying. This revelation was also prepared by seriously entertaining the question of what the Masters might have thought about K. Probably I looked to them to extract myself from my self-imposed conundrum in regards to K. This set of experiences, maybe better named a genuine crisis of faith, paved the way to get involved in what I then believed to be a post-Theosophical group connected with the same Masters to which Blavatsky, Leadbeater and K were allegedly connected. And from this corner came an even more devastating critique of K.ix

But, while repudiating the metaphysical claims of K’s status and the claims regarding the purity of his teachings, I knew he had said many a true thing, and I was not ready to completely throw him overboard. After some intensive research in the mid-90s I wrote the Krishnamurti and the World Teacher Project: Some Theosophical Perceptions paper, trying to be objective and comparative. I also released on my newly constructed web site Alpheus two pamphlets to lay out my own personal, metaphysical views. On this site I tried to present as many resources as possible for people to investigate these matters for themselves.

Then philosophy struck again and I started another round of intensive studies of phenomenology, now with the Heidegger expert Theodore Kisiel, who I found at Northern Illinois University just 30 miles west from where I lived. This resulted in the above mentioned paper “The Relevance of Phenomenology for Theosophy”, which was also the basis for a class I taught on phenomenology at the Theosophical Society in America.x In the paper there is a sub-section on K, which spells out my intended philosophical research program to deal with K.xi

As regards the subtleties themselves involved in this endeavor I submit the following two analyses of K’s experiences in which I pull from both phenomenology and Theosophy. The two analyses are at loggerheads and a deeper investigation is necessary (see way below) to find the angle from which both accounts can be seen as true. This then might result in a deeper understanding of our ambivalence towards K.

Analysis I: The Sympathetic Theosophical View

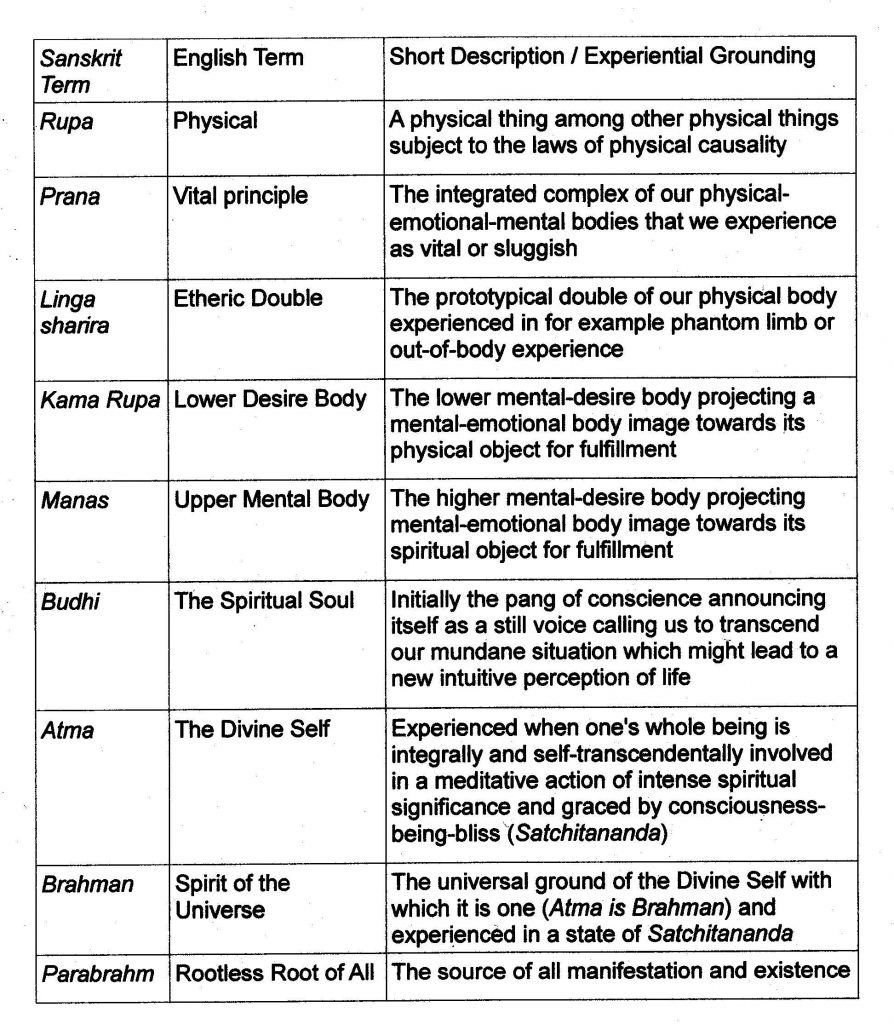

The origin of this account was in several discussions conducted with Theosophists on awareness and its connection to implicit and explicit self-awareness and how such ideas might apply to K. At the same time we used a lot of Theosophical concepts to further elucidate K’s experiences and states of mind. The following is a table of the Sanskrit and English terminology used by many Theosophists, to which I added descriptions in an experiential terminology.

Fig. 2. Table of Sanskrit and English Terms

for Aspects of Human Beings

In terms of states-of-consciousness one could differentiate within Krishnamurti’s own experiences and history–as he related them publicly and privately in his own words–the following ‘states,’ to which I will attach some of the above discussed Theosophical and/or Sanskrit terms:

a) In the years leading up to 1922 K was often critical, rebellious, doubtful of his expected role, even sometimes depressed. One could say that he was subjected to regular, mundane experiences of Kama-Manas with sometimes some Buddhi poking through.xii

b) This attitude was radically altered by his re-conversion or re-dedication to his mission inspired by a Mahatmic message received in Sydney in June 1922. With a touch of skepticism Lutyens wrote that the message was ” ‘brought through’ by Leadbeater”. The opening sentences read:

Of you, too, we have the highest hopes. Steady & widen yourself, and strive more & more to bring the mind & brain into subservience to the true Self within.xiii

Inspired by the message K wrote five weeks later that “I am going to get back my old touch with the Masters & after all that’s the only thing that matters in life & nothing else does”.xiv One could say that in a moment of vision the Buddhi principle was prevailing over his Kama-Manas.

c) From then on K engaged in a regular regime of meditation. This could be conceived as the stabilizing of the Buddhic in silence by subsuming the lower bodies. Of his intention K wrote that ” . . . I had to harmonize all my other bodies with the Buddhic plane . . . To harmonize the various bodies I had to keep them vibrating at the same rate as the Buddhic . . .” xv

d) In August 1922 in Ojai saw the start of the painful and dramatic Process. This could be conceived as if the Masters were purging K’s body through occult means while K himself was mostly absent in a state of out-of-body experience. K also had experiences of his Kundalini rising, i.e. the awakening of his spiritual energies in the Root Chakra at the base of the spine and rising towards the Crown Chakra at the top of the head.xvi Occasionally, when K’s soul was OBE (went off”), a child-like sub-personality would express itself about the pain the body was going through. In Theosophy this is called the “physical elemental” and is a part of one’s Kama Rupa (lower desire body) connected to the physical body.xvii

e) After a year and a half, and back in Ojai again, the Process culminates in the opening of both the Crown and Third Eye Chakras making it possible for K to have conscious communion with the Masters and a clear certainty about his mission.xviii At this moment one could say that the Buddhic principle had fully overcome and subdued the Kama-Manas.

f) Then K experienced initially a traumatic, but finally a very transformative experience. On his way to India in November 1925 he received news of the death of his brother and life companion Nitya. In and through the mourning process K seemed to have purged the last vestiges of doubt and attachments. It was a deepened vision born out of suffering. K also expressed that he was unified in spirit with Nitya.xix This could be explained by the idea that the brothers were Twin Flames, a neo-Theosophical concept originating in the I AM Movement.xx

g) On December 28, 1925 occurred the first manifestation of Maitreya in Adyar, India at the grounds of the international headquarters of the Theosophical Society during a meeting of the Star in the East. Many claimed, and even watched clairvoyantly, that Maitreya spoke through K, something K himself confirmed afterwards.xxi The openness and trust involved were enabled by K’s stable Buddhic state of awareness, making it possible for a realized Mahatma to temporally ‘take over’ K’s vocal cords at that level.

h) Around 1927 K starts to reframe his mystical-developmental arc with the intentionally vague term “my Beloved“. For K the Beloved was the ultimate goal to be united with, like attaining a mountain top or entering a flame.xxii As long as this goal had not yet been attained one could conceive this as the Buddhic sighting of Atman, i.e. the individualized spiritual soul has the vision of the all-pervasive divine self.

i) K becomes the Beloved in moments of intense mysticism. He sees the Beloved as everywhere and within everything. For K the Beloved was “the open skies, the flower, every human being” including all the masters, even Maitreya and Buddha, “and yet it is beyond all these forms”.xxiii Here it could be argued that some fusion of the Buddhic with the Atman was established. These pronouncements became the stepping stones for K to go beyond Theosophy into his own unique interpretation of his states of mind, but K’s statements also became stumbling blocks for the more doctrinaire Theosophists in their evaluation of K, especially surrounding the question whether he was fulfilling the Project or not.

j) By 1961, and maybe even earlier, K has deep experiences of ‘benediction,’ ‘otherness,’ and ‘immensity.’ He referred to these experiences early on in his Notebook as “that fullness of Il L.”, i.e. Il Leccio, the name of a Tuscan villa belonging to K’s friend Vanda Scaravelli.xxiv This might have been the place where these experiences started when he visited it on a regular basis just after WWII, though he had stayed there once before in 1937. This experience seems to have been unexpectedly coming and going, though in differing intensities. Again, in more Sanskrit terminology one could say he was experiencing Sat-chit-ananda, the combination of Being (Sat), Consciousness (Cit) and Bliss (Ananada), and, maybe best caught in the phrase ‘blissful consciousness of being’.

k) K’s state of high intensity meditation culminates one night in the middle of November 1979 in reaching “the source of all energy”, which he perceived as “the ultimate, the beginning and the ending and the absolute” as he stated in a specially dictated account of that momentous event. In Hindu philosophy Atma (the soul) is equated with Brahm (God). As K was arguably at that level of consciousness already, it could very well be that the ‘source’ was beyond Brahm, i.e. Parabrahm, the highest, supreme principle. On the other side it has to be mentioned that in the same statement K cautioned his readers that his experience “must in no way be confused with, or even thought of, as god or the highest principle, the Brahman, which are the projections of the human mind out of fear and longing, the unyielding desire for total security.”xxv

So far the identifiable steps K took on his spiritual-developmental arc and the possible Sanskrit terms to describe them. Excluded in this enumeration are the states of consciousness relevant to K as a teacher, which had its own developmental stages.

What has been gained with this differentiation? First of all it has to be noted that, though words fall short in giving complete descriptions, these states of consciousness are different enough that they can be expressed in different concepts. Secondly, that K was aware of these differences and was the first one to suggest the appropriate non-technical concepts. Thirdly, as skilled Theosophists can do, parallels can be found with Theosophical and Sanskrit terminology.

The fact that K was aware of these experiences and could describe them afterwards indicates that something like a ‘self,’ or something ‘self-same,’ was enduring during these experiences, at least from the experience itself up to the moment of having them written down. For me this also indicates that something implicitly self-aware in the experience became explicitly so in the wording and that memory had some function in this transition. In the context of this article such pondering is not that relevant, though it has to be mentioned that K’s mystical experiences are grist to the mill of an existential-phenomenological interpretation to be pursued in other venues.xxvi

Analysis II: The Critical Theosophical View

The critical Theosophical view would accept the above development of K until around 1927. At that point a sharp divergence can be noticed and it all seems to hinge on the interpretation of what K called his Beloved.

Around 1927, when Annie Besant proclaimed to the world the return of the Christ in the body of K, a process had commenced within Krishnamurti which made it more and more difficult for Maitreya to overshadow him. Besant’s understanding that K’s consciousness was blended with Maitreya’s and that a part of Maitreya was blended with K is incorrect. K became his ‘own’ and the only fusion taking place was K and his Beloved, not K and Maitreya.

In K’s own view he was leaving the Masters behind, and in Maitreya’s view, as per David Anrias, K took certain initiations under some very advanced and coldly intellectual nature spirits or Devas. Maitreya (per Anrias) specifically stated:

You who have studied the horoscope of Krishnamurti know that he is incapable of compromising with the past; also that he was reinforced in his seemingly destructive work by those great Devas of the Air, who, under direction of the Lords of Karma, are helping Man to polarize himself towards spiritual rather than material conquests.

In order to co-operate more completely with the Devas, Krishnamurti took initiations along their line of evolution. The essential nature of these Devas, used as agents of the Great Law, being perforce impersonal and detached, it came by degrees to influence his whole point of view, making him appear unsympathetic and even inhuman. Furthermore, since he had attained these initiations in the causal body by a positive effort of consciousness, it became all but impossible for him to be used any longer as my medium.xxvii

K’s account, based on experience and seen from the inside out, seems to accord with Maitreya’s account, seen from the outside in. Only their valuations differ. The crucial point, which made these developments possible, was that the Project was a unique experimental one, never done before with any previous preparations for an Avataric happening. Because it was experimental it had the chance for not working out as was hoped. And I thought anno 2005 that it had failed.

The failing factor, and here I use the word ‘failing’ in a completely factual and non-judgmental sense, was that K’s body could not endure the strain, even though it could endure a quite inconceivable amount of pain and stress. This shortcoming of K’s body was nobody’s fault.xxviii Where K was at fault was in re-interpreting the Project according to his own emerging understanding, which became increasingly at odds with Theosophy.

This understanding was–and this is the core of the problem–a reflection of K’s non-acceptance of the failure of the Project and his decision to carry it out anyway, even if that meant arrogating, through creative conceptual massaging, the World Teacher title while tossing out the whole spiritual-conceptual framework of Theosophy, including Masters and initiations.

Seen from this perspective, and mixing in some psychoanalysis, K’s teachings are one long continuous justification of that one fateful decision he made. Because of his charisma and appeal to flawed deep motives within ourselves similar to his own, he was successful in converting quite some people to his view and providing them thereby with the justifications to leave behind the deeper mystical understandings of life provided by Theosophy.

The only exceptions would be those Krishnamurtian Theosophists and Theosophical Krishnamurtians who have taken on a mighty spiritual-intellectual struggle to straighten out the many inconsistencies between the two views, for which I only have the greatest respect, even while contributing my own contrarian view.xxix

The Sympathetic and Critical Views Interpreting Each Other

Though both accounts are obviously quite different, I can see some of the possible strategies to explain the sympathetic analysis from the perspective of the critical one, and other way around.

First Strategy

To start with the first strategy–the refutation of the critical view by the sympathetic view–I think that K himself already gave some indications about possible interpretations. These mostly come down, as I pointed out in “K and the World Teacher Project”, to ad hominem attacks: the listener just doesn’t get it, because he/she doesn’t want to or has an alternate agenda. Many variations can be found on that theme. Or Theosophists might fall back on more esoteric ideas like the existence of imposter Masters who deceived critical Theosophists like Scott, Anrias, Hodsen and others. Or, some will argue, they were just hallucinating. The possibilities are vast and have not yet been presented in an exhaustive manner. What is safe to state here is that the Scott-Anrias line of criticism has been overall neglected except for the British Theosophist and writer Jean Overton Fuller, with whom I have had some exchanges on the subject, and German writer Peter Michel. Both took some pains to engage the Scott-Anrias material. Fuller was quite critical and thought that the Scott and Anrias writings was fictional and that some of its allegedly enlightened characters spouted “nonsense”.xxx Michel took them quite serious, but then tried to combine contradictory positions, which complexity I will leave for the aficionados to think through.xxxi What is quite fascinating is that K in 1936 responded to a question in which its criticism of K was lifted from a book by Scott. His answer was, that,

People who write books of this kind are consciously or unconsciously exploiting others. They have axes to grind, and having committed themselves to a certain system, they bring in the authority of a Master, of tradition, of superstition, of churches, which generally controls the activities of an individual.xxxii

So far for the manner in which all these Theosophical criticisms were and could be parried.

Second Strategy

The second strategy–and the real challenge for me–is to incorporate and re-interpret K’s development and experiences as presented in the sympathetic view, into the critical view. Is it possible for a person, in this case K, to have all that charisma, deep mystical experiences and profound teachings even while having failed a crucial test and having repudiated the Masters and Theosophy? This was, anno 2005, the leading question for me. Two points I will make in this context, one about skill acquisition as a time-consuming phenomenon and the second about K’s critical statements regarding Theosophy and the Masters.

One of the lines of investigation is to get a grip on the idea of skill acquisition as that pertains to displaying charisma, attaining deep levels of meditation and being able to talk to an audience without notes. The idea is that these are skills developed over a long period of time, possibly including many lives, and are not the side effects of a passive state of consciousness through which something otherworldly comes through, though apparently it was perceived as such by K himself and others.

Phenomenology can help here again, because it has made some attempts to differentiate the different levels of skill acquisition. Especially the American Heidegger expert Hubert Dreyfus is quite active in this field. For example the beginning of his paper “Could Anything Be More Intelligible than Everyday Intelligibility?” has some very pertinent things to say about action at the highest levels of human endeavor, i.e. public action based on visionary experiences, which is what K, and also HPB and others, were all about.

The crux of the matter is a correct understanding of the highest level of skill, i.e. expertise or the Aristotelian virtue of Phronesis, in which an actor has a uniquely appropriate response to a unique situation. Important here is to realize that this is a very high skill only obtained through time and experience, not through some methodless, instantaneous transformation as K wants it. Further, this analysis of skill acquisition might also shed light on the whole initiatic process, which might be nothing less than a gradual and integrated development of mental, volitional and affective skills, a process through which K went himself between 1911 and 1925, only to repudiate it, when he was arguably at a quite proficient level of spiritual skillfulness, if I can put it like that.

Meanwhile the more or less passive part of the Project–i.e. K’s overshadowing by Maitreya–can also be re-interpreted along phronetic lines, because it involved K’s skill to maintain a certain level of attunement and Maitreya’s skill to then ‘overshadow’ K and bring forth the needed teachings for the new epoch. As you can see the idea has some fruitful applications in clarifying many of the subtleties involved in the K-problematic.

Though the above line of reasoning with the help of a phenomenology of skill acquisition could be used in both the sympathetic and critical account of K, I think its crucial importance is to make clear that K’s all-or-nothing, methodless methodology to get enlightened and his repudiation of the gradual initiatic process was erroneous. It therefore strengthens the critical view.

The second point is about the really big challenge for the sympathetic view of K to come to terms with K’s very critical remarks about Theosophy, the role of the Masters and the initiatic process. I created a double column juxtaposition of the views of Theosophy and K on numerous subjects titled “Comparison between Theosophy and Krishnamurti” and would present that as exhibit A in making the case that it would be extremely improbable that someone working with the Masters, even to the point of having ‘melded’ his consciousness with one, would make such denunciatory remarks.xxxiii Only the Theosophically critical view of K would be able, and in a very easy manner, to explain those remarks–after all–this view is based on the idea that K repudiated the whole Theosophical set-up for which he gave ample evidence. Let’s listen to what he said.

JK: You may deceive yourself by saying, “What you say and what I [Theosophist] believe are the same. They’re the two sides of the coin.” You may say what you like; but that is mere self-deception.xxxiv

JK: Sirs, these two things are wholly different: what you [Theosophists] are thinking and doing, and what I am talking and doing. The two cannot combine. Your whole system is based on exploitation, on following authority, on belief and faith. . . . What you are doing and what I am doing are two totally different things that have nothing in common.xxxv

My exhibit B would be the working paper “Krishnamurti on Theosophy” composed by Hans and Radhika Herzberger for the Rishi Valley Study Centre, a study retreat run by the Krishnamurti Foundation of India. This is an exhaustive list of relevant quotes by K and also has a very good introduction discussing different theories applicable to the relationship of K and Theosophy, which I will address in another article.xxxvi One of the more clear quotes presented is:

Q: I have studied Theosophy very deeply and …I say that your wisdom is essentially the truth of Theosophy.

JK: You may study profoundly all the Theosophical books; but your conception of wisdom is utterly false. . . . You gather dust from books and call it wisdom. I speak of a natural wisdom, beyond all books. . . . To me your theories are utterly valueless.xxxvii

Numerous similar quotes can be found, especially in the years 1927 to 1934, and which summation might be best expressed by Dominique Johnson in his article processing the divergence between K and Theosophy:

Jiddu Krishnamurti utterly rejected the convergence of his thought and Theosophy, and his wishes should be respected. Contemporary Theosophists have to let go of Jiddu Krishnamurti, and trying to reconcile or find a convergence of Krishnamurti’s thought and Theosophy (italics in original).xxxviii

Notwithstanding K’s strong statements and the many irreconcilable differences, Theosophists and, for that matter, any researcher, can find some points of convergence, if not agreement. In the double column I placed such under the headings of God, Consciousness and Ego. The Argentinian-American Theosophical scholar Pablo Sender wrote a very perceptive article on these agreements and also presented his own ‘two-aspects’ or ‘two sides of the same coin’ argument to reconcile the differences, though is not engaging–let’s call it– the Herzberger material.xxxix

In sumary I think that, provided one likes to see the problematic from a Theosophical point of view, the most plausible theory is that K drifted away from Theosophy not only because Theosophists started having increasingly fictive notions of the Project, but that K had no more use nor sympathy for any kind of esoteric thinking whatsoever. The only baffling thing was that he still claimed, in ever more subtle and evasive wording, the mantle of World Teacher.

Additional Questions and Answers

The foregoing is an introduction to answer some specific question:

1). What was K’s experience of Benediction actually?

2). Was K really enlightened or not?

3). What is true and what is false in K’s teachings?

4). Was K living his own teachings?

1). First the Benediction. Going back to the sympathetic view of K presented earlier I can indeed see it as an experience of Satchitananda (blissful consciousness of being) operative at the Buddhi-Atman level. As many have reported similar experiences, and I have partaken of this myself, it does not seem to be so extraordinary by itself. What is unique in K’s case is the apparent depth of his experience, its ongoing nature, and the simple and poetic language in which he was able to convey its intensity. The experience doesn’t indicate a necessary reference to Maitreya, the Masters or God.

Aryel Sanat in his esoteric study of K seems to think that the experience is somehow indicative of an intimate communion with Maitreya. He tries to make the case that all of K’s initiatic experiences like the Process and the Kundalini rising were conducted by the Masters; that K’s experience of the Beloved was an experience of the Lord Maitreya because the Beloved had to be equated with that Master as K seemed to imply; and that the experience of the Beloved was the same as the Benediction, therefore Maitreya was with K throughout his life and therefore at least co-responsible for the teachings.xl This series of equations is quite a stretch and I think he errs. Of course Kundalini was involved, especially in the preparatory stages of the Process. A differentiation has to be made between the Process, which seems to be a painful purging of the lower bodies in which other intelligences might be involved like Masters or Devas, and the Benediction, which is an experience of cosmic bliss beyond the Process and beyond other intelligences. Initially K included the Masters in his concept of the Beloved, but after abjuring the Masters and Theosophy in the early 1930s this inclusion can hardly be maintained.

Anno 2005, I saw K’s capacity for having these experiences as rooted in a very subtle skill developed over many lifetimes and greatly helped by his intimate relationship with the Masters in the early stages of his last life.

2). Second, it is hard to establish the idea whether K was enlightened or not. It all depends on one’s definition of enlightenment of course and as long as we are not enlightened ourselves, it could be argued we really do not know. My position is that he attained some superior levels of spiritual skill, but got stuck, though he himself thought he had reached the highest level of ego-less being. For some he might be a genuine and really helpful beacon of light for a while, but beyond a certain point his role becomes that of a very subtle pied-piper leading souls to an impasse similar to his own. The really enlightened teachers for humanity are the Ascended Masters. I believed that Buddha, Kuthumi, El Morya, Jesus, Saint Germain, Nicholas and Helena Roerich and Guy Ballard were all at that level. I did not know about Ramana Maharshi and Nisargadatta Maharaj. So, for me, K could not be considered enlightened.

3). Sorting out the true from the false in K’s teachings will be an arduous task. His disregard for other religions and philosophies is quite unacceptable. Most of them are a mixed bag, as are his own teachings. I think he can be very perceptive in his analysis of certain existential themes like fear, desire, death, escapism, etc. But he can be quite wrong and simplistic in his analysis of the function of thought and understanding. Also his analysis of ego-genesis as solely depending on thought, while leaving out the necessary component of consciousness reflecting upon itself, is quite inadequate. And he really starts fumbling when he equates the essence of thought with that of matter. He is also quite deficient in finding a realistic balance between gradual developments and possible ‘quantum leaps’ in spiritual development. He also reduces issues, far more often than acceptable, into black-white dichotomies, which suggests to me that he is a little bit infatuated, without knowing so, by the power of logo-centric thinking. This is all the more ironic because of his purported deep insights into the nature of thought. There are pearls to be found in his thoughts, but it is a dangerous picking.

4). One other important issue to discuss is whether or not K was living his own teachings. A lot is involved, beginning with the problem of what it means in the first place to “live a teaching”. The phrase seems to imply that the teaching is the more important part of the equation, and that it would be possible to live according to the teaching. The problem with K seems to be that he doesn’t give much of a teaching to live by in the first place. If there are specific instructions, they are very commonsense and obvious, like “don’t smoke,” or they are so general that nothing specific is implied, like “be aware”. I don’t think he ever said “always tell the truth” or “don’t bed your friend’s wife,” etc, which would be obvious grounds to accuse him of hypocrisy. He might have trespassed conventional norms of behavior, but those norms are ours, not his. As a highly creative and observant person, K was bound to do things many would not understand, or find immoral, but again, that might be more due to our own shortcomings than his.

Now, if one sees his live as more important than his teachings, and instead of measuring his live by the content of his teachings, one could try to assess if his teachings are an expression of his life. Here I can see three possible perspectives from which to answer that question, which will be elaborated below: Either a) we see K’s life as he wanted us to see it, or b) see his life from a sympathetic Theosophical view, or c) from a critical Theosophical point of view, as I laid these out above.

a). In the first case it could be argued that his life is lived on such a high, subtle, virtuous and trans-rational level, that whatever he teaches, his verbal expressions will never really express what he really wants to express, though he can get very close. And, as he keeps trying and trying, he is bound to make an excusable mistake or two here and there. And as his teachings are on a lesser level than his life, you can not throw those teachings back into his face, as he would say himself. And, as far as some of his questionable behavior is concerned, one could make a similar defense by making the case that, as his actions come from his seeing, and we do not see how he sees, we can hardly criticize him. And even if he would make a mistake, we should give him some leeway for such, for he keeps experimenting for the sake of truth and humanity and is therefore bound to make some mistakes. In short, there is enough material in K’s life, and enough arguments shaped by his teachings, to construe K such that he is indeed the almost infallible enlightened world teacher as many believe him to be.

b). In the second case we enter into the thought realm of thinkers like Radha Burnier, Aryel Sanat, Jean Overton Fuller and Peter Michel, all of whom are sympathetic to K and try to see him also from an esoteric perspective. The only one having some doubts about K is Michel for he is aware of the Scott and Anrias perspective, which I analyzed in my review of his book on K.xli

Anyway, the crux of the matter is that they see K’s life as intimately bound with his teachers, the Theosophical Masters of Wisdom, and his teachings as, at least, sanctioned and possibly suggested and even formulated, by them. Seen in this way his life is that of an Avatar bringing a new and superior message. And the new teaching is superior to Theosophy, which might therefore be legitimately abandoned here and there. There are of course some other interesting strategies deployed to reconcile their esoteric perspective with K’s criticisms of the same. In short, his life has a transcendental dimension few of us are aware of, and his teachings are better understood if that dimension is taken into account.

c). The last perspective, the one I thought was correct anno 2005, is seeing K’s life in the perspective of his, first attempted, then failed and then pretended, messiah-ship, fueled by a subtle spiritual and intellectual pride he never overcame. In this critical perspective I stated somewhat dramatically that “K’s teachings are one long continuous justification of that one fateful decision he made” of “non-acceptance of the failure of the Project and his decision to carry it out anyway.” I think it is this perspective that will be able to reconcile the many contradictions and mysteries in his life and teachings and see both as being in ‘harmony,’ for both are terribly flawed. In short, one could say that K did live his teachings and his teachings do reflect his life, but not in the way most of his Theosophical and non-Theosophical followers would like to see.

Postscript Anno 2019

A few years later, in 2008, I started having doubts about the Theosophical worldview itself. This doubt was set in motion by a deeper investigation of the life and teachings of the founder of Theosophy Helena Blavatsky, which investigation itself was caused by my intensified engagement with Theosophy and my need to figure out some of its basic assumptions. In the years 2008 and 2010 I volunteered at the Theosophical retreat camp Far Horizons in the Sequoia National park after which I lived for more than a year at the Theosophical Society in America headquarters where I conducted some classes on esoteric history and had the time to write a large article engaging Jean Overton Fuller on the issue of the Scott & Anrias writings, the research for which focused on one of the Masters by the name of Narayan.xlii The article was written again as objective and neutral as possible, though I did make the case that both Mrs. Fuller and myself should still divulge, as a matter of fairness to our readers, our respective metaphysical positions as such would inevitably give some coloring to our writings.

In that spirit I wrote a little article telling my story of how the Scott and Anrias material came into my life and what radical changes that caused.xliii I do not want to burden this article with my mind’s gyrations, but my readings resulted in a very skeptical position towards Blavatsky and her Theosophy. What I learned was that from the very start of Blavatsky’s appearance as a major writer in the genre of Western esotericism many journalists, academics and fellow esotericists were skeptical of her and wrote many an article, report or book challenging her veracity. Arguably this string of challenges to Theosophy culminated in Marion Meade’s 1980 Madame Blavatsky: The Woman behind the Myth, which is a bit flawed biography bringing together a wealth of sources, which have to be studied and evaluated by themselves.xliv

My engagement with the primary sources triggered a second crisis of faith resulting in the crumbling of my belief in the whole esoteric-occult edifice build up in the last four or five hundred years in and by the spiritual stream of Western Esotericism, as academics call it, including the ideas by Scott and Anrias which were so important in my critical view of K.

What gradually filled the vacuum, and also actively pushed Theosophy out, could be blamed, if I may simplify the process a bit, on the following three books, each of which are anchored in a more naturalist, evolutionary view of life: Richard Dawkins’ The Selfish Gene, Julian Jaynes’ The Origin of Consciousness and Into the Flow by Dorion Sagal and Eric Schneider. It is not the intention in this article to work out their thoughts (including many others’) in their mutual coherence, but I made a start in an article about Jaynes in which I also found room for a new appreciation for K as a very secular ‘enlightened’ being with a profound, challenging, this-worldly message shorn of any esoteric or transcendental elements.xlv

Of course I had to reassess my previous views and writings on K and had to decide whether to throw them away and delete the portions on my web site inspired by them. In the end I decided to leave it all intact, idiosyncrasies and all, and start with a new platform dedicated to “Critical History” with a link to the ‘old Alpheus’, where you can find all that former, esoteric material dedicated to “Esoteric History” and my critical Theosophical view of K.xlvi

In conclusion, I believe now that there was never a transcendental cause working in K’s background, and that, even if the grand Project was based on either false believes or an intentional experiment, K came out of this as a truly transformed human being opening vast possibilities for others to also experiment with, though with caution. As far as my own positions regarding K developed, I went from being a K purist with some sympathy for Theosophy, to a Theosophical view very critical of K, to now a secular, sympathetic view of him, though not without some philosophical criticism of his teachings

Bibliography

Agrawal, M. M. 1991a. Consciousness and the Integrated Being: Sartre and Krishnamurti. Shimla, India: Indian Institute of Advanced Studies.

——-. 1991b. “Nothingness and Freedom: Sartre and Krishnamurti”. Journal of Indian Council of Philosophical Research, 9/1: 45-58.

Anrias, David. 1932. Through the Eyes of the Masters: Meditations and Portraits. London: Routledge. [For more information and excerpts see Dossier]

–——. 1933. Adepts of the Five Elements. London: Routledge.

Dawkins, Richard. 1976. The Selfish Gene. Oxford: Oxford UP.

Dreyfus, Hubert. 2000. “Could Anything Be More Intelligible than Everyday Intelligibility? Reinterpreting Division I of Being and Time in the Light of Division II.” In Faulconer, James E. & Wrathall, Mark A. (Eds.), Appropriating Heidegger. Cambridge: Cambridge UP. 155-174.

Fouéré, René. n.d. “Krishnamurti et l’Existentialisme”. In Linsen, Robert (Ed.), Krishnamurti et la Pensée Occidentale. Brussles: Editions Être Libre.

Fuller, Jean Overton. 1997. Letter from Jean Overton-Fuller to Govert Schuller. 23 July 1997. Alpheus.

——-. 1998. Cyril Scott and a Hidden School: Towards the Peeling of an Onion. Theosophical History Journal, Occasional Paper VII.

——-. 2003. “Scott and Anrias: Wood and the Blind Rishi“. Chapter 20 in Krishnamurti & The Wind. London: The Theosophical Publishing House. 165-173.

Gunturu, Vanamali. 1998. Jiddu Krishnamurti’s Gedanken auser der Phaenomenologischen Perspective Edmund Husserl’s. Ph.D. Thesis. Frankfurt: Peter Lang.

Hammer, Olav. 2004. Claiming Knowledge: Strategies of Epistemology from Theosophy to the New Age. Leiden: Brill.

Hanegraaff, Wouter J. 1998. New Age Religion And Western Culture: Esotericism In The Mirror Of Secular Thought. New York: SUNY.

Herzberger, Hans and Radhika. 1995. “Krishnamurti on Theosophy“. Reference Materials on Krishnamurti’s Teachings. Working Paper #4. Rishi Valley Study Centre.

Jaynes, Julian. 1976. The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Jinarajadasa, C. 1930. “Krishnamurti’s Message“. Adyar Pamphlets No.134. Adyar: Theosophical Publishing House.

Johnson, Dominique, 2017. “Jiddu Krishnamurti repudiates the Convergence of Theosophy and his Teaching“. The American Minervan web site, 13 July 2017.

Johnson, K. Paul. 1990. In Search of the Masters Behind the Occult Myth. Self-published.

——-. 1994. The Masters Revealed: Madame Blavatsky and the Myth of the Great White Lodge. SUNY Press.

——-. 1995. Initiates of Theosophical Masters. SUNY Press.

Keidan, Bill. 2000. “What really happened to J. Krishnamurti?” Alpheus, January, 2000.

Kisiel, Theodore. 2005. “The Future of Being: Is Heidegger Its Prophet?” Lecture on CD. Wheaton, IL: The Theosophical Society in America.

Krishnamurti, Jiddu. 1929. “The Dissolution of the Order of the Star”. International Star Bulletin, (September 1929): 28-34. Also titled “Truth is a Pathless Land”.

——-. 1972. Early Talks IV. Bombay: Chetena.

——-. 1976. Krishnamurti’s Notebook. New York: Harper & Row.

——-. 1991. The Collected Works of J. Krishnamurti. Volumes 1-18. Ojai, CA: Krishnamurti Foundation of America. Also Delhi: Banarsidass, 2014.

Lutyens, Emily. 1957. Candles in the Sun. London: Rupert Hart-Davis.

Lutyens, Mary. 1976. Krishnamurti: The Years of Awakening. New York: Avon Books.

——-. 1983. Krishnamurti: The Years of Fulfillment. New York: Avon Books.

——-. 1988. Krishnamurti: The Open Door. London: John Murray.

——-. 1996. Krishnamurti and the Rajagopals. Ojai, CA: Krishnamurti Foundation America.

——-. 1990. The Life and Death of Krishnamurti. London: John Murray.

——-. 1995. The Boy Krishna: The First Fourteen Years in the Life of. J. Krishnamurti. Brockwood Park, UK: Krishnamurti Foundation Trust, England.

Meade, Marion. 1980. Madame Blavatsky: The Woman behind the Myth. New York: Putnam’s Sons.

Michel, Peter. 1995. Krishnamurti: Love and Freedom (Approaching a Mystery). Woodside, CA: Bluestar Communications.

Oliveira, Pedro. 2008. “Blavatsky and Krishnamurti: A Timeless Dialogue”. The Theosophist 129/12 (September 2008): 456-464

Robertson, John K. “Aquarian Occultist: The Life and Teachings of Geoffrey Hodson” (unpublished MS, 1971), 190-198.

Sanat, Aryel. 1988. “The Secret Doctrine, Krishnamurti & Transformation”. The American Theosophist, 76/5 (May 1988): 133-143.

——-. 1999. The Inner Life of Krishnamurti: Private Passion and Perennial Wisdom. Wheaton, IL: Quest Books.

Sartre, Jean-Paul. 1957. The Transcendence of the Ego. New York: The Noonday Press.

Schneider, Eric D.& Sagan, Dorion. 2005. Into the Cool: Energy Flow, Thermodynamics, and Life. University of Chicago Press,.

Schuller, Govert. 1997a. Krishnamurti and the World Teacher Project: Some Theosophical Perceptions. Theosophical History Journal, Occasional Paper V.

——-. 1997b. “Krishnamurti: An Esoteric View of his Teachings“. Alpheus, 1997.

——-. 1997c. “The Masters and Their Emissaries: From H.P.B. to Guru Ma and Beyond”. Alpheus, 1997, 2nd edition 1999.

——-. 1998. Response to Mrs. Fuller. March. 1998. Alpheus.

——-. 2004a. “Theosophy and Krishnamurti: Harmonies and Tensions”. Lecture at The Theosophical Society in America. Wheaton, IL: TSA. [Audiofile forthcoming] [Handout]

——-. 2004b. “Comparison between Theosophy and Krishnamurti“. Double Column Comparison with Footnotes. Alpheus, 2005.

——-. 2005a. “The Relevance of Phenomenology for Theosophy“. Alpheus, April 2005.

——-. 2005b. “Krishnamurti Discussion: Exchange of e-mails between Anonymous and Govert Schuller in November 2005″. Alpheus, November 2005.

——-. 2008a. “Jean Overton Fuller, Master Narayan and the Krishnamurti-Scott-Anrias Issue“. Theosophical History Journal, 14/1 & 2 (January-April 2008; Double issue):11-46.

——-. 2008b. “The Scott and Anrias Material in my own Historical Situatedness“. Alpheus, January 2008.

——-. 2010. “Review of Peter Michel’s Krishnamurti: Love and Freedom“. Alpheus, 3 Feb 2010.

——-. 2014. “The Jaynesian Paradigm and Beyond“. Alpheus, January 2014.

——-. 2015a. “By Way of Husserl: A Phenomenology of Duchampian Art“. Term Paper; Art History 454; Spring 2014; The Duchamp Effect; Prof. Barbara Jaffee; NIU, DeKalb, IL. Alpheus, February 2015.

——-. 2015b. “The Inner Life of Krishnamurti“. Letter to the editor of Quest magazine, Winter 2015. Alpheus, December 2015.

——-. 2019a. “Theosophy and Krishnamurti: Harmonies and Tensions“. Text based on 2004 lecture at the Theosophical Society in America. Alpheus, 2019. [Forthcoming]

——-. 2019b. “Gradiance: The Mother of all Reductions”. Alpheus. [Forthcoming]

——-. 2020. The Possibility Conditions of Narrative Identity. Masters by Research in European Philosophy; Dissertation; University of Wales [Forthcoming].

Scott, Cyril. 1932. The Initiate in the Dark Cycle. London: Routledge. Published anonymously under the authorship of “His Pupil”. [For more information and excerpts see Dossier]

Sender, Pablo. 2004. “Krishnamurti’s Teachings and Theosophy“. The Theosophist, 126/2: 93-100.

Thakar, Vimala. 1966. On an Eternal Voyage. Hilversum, Netherlands: E.A.M. Frankena-Geraets.

van der Leeuw, Jacobus Johannes. 1930. “Revelation or Realization: The Conflict in Theosophy”. Amsterdam: Theosofische Vereeniging Uitgevers Maatschappij.

Vedaparayana, G. 2003. “The Conditioned and the Unconditioned Mind: J. Krishnamurti’s Perspective.” Indian Philosophical Quarterly, 30/4: 525-552.

Endnotes

i Schuller, 1997a: 1-2.

ii Schuller, 1997b & Schuller, 1997c.

iii The original presentation of the e-mail exchange is in “Krishnamurti Discussion“.

iv or more details see my letter to the editor of Quest magazine “The Inner Life of Krishnamurti“.

v See “The Relevance of Phenomenology for Theosophy“, especially the section on Krishnamurti.

vi See “By Way of Husserl: A Phenomenology of Duchampian Art“.

vii See The Possibility Conditions of Narrative Identity . (Forthcoming)

viii For an autobiographical article addressing this event see Schuller 2008b.

ix See the section “Elizabeth Clare Prophet” in Schuller, 1997a, 15-16.

x The class was preceded by a public lecture by Prof. Kisiel, “The Future of Being: Is Heidegger Its Prophet?”

xi Besides this list I composed another one at the end of my on-line introduction to K.

xii Lutyens, 1976, chapter 10 “Doubts and Difficulties”, chapter 14 “Critical and Rebellious”, 111-2, 138-9.

xiii Idem, 147, Chapter 18 “The Turning Point”.

xiv Idem, 152. Italics in original.

xv Idem, 152, 158.

xvi Idem, 166.

xvii Idem, 166, 175, 176, 177, 188.

xviii Idem, 186.

xix Idem, 220.

xx See for example “Twin Flames and Soul Mates“.

xxi Lutyens, 1976: 223.

xxii Idem, 247.

xxiii Idem, 249.

xxivKrishnamurti’s Notebook, 11-12.

xxv Lutyens, 1983: 237-8.

xxvi For this phenomenological interpretation of Krishnamurti’s experiences and teachings see Fouéré, n.d.; Agrawal, 1991a & 1991b; Gunturu,1998; Vedaparayana, 2003; and Schuller, 2005a;

xxvii Anrias, 1932: 66.

xxviii This line of thought was developed by Geoffrey Hodson. See Robertson MS, summarized in Schuller, 1997a: 11-13.

xxix To the many Theosophists mentioned in my 1997 paper I would now add C. Jinarajadasa (1930), J.J. van der Leeuw (1930), Bill Keidan (2000), Pablo Sender (2004) and Pedro Oliveira (2008).

xxx My discussion with Fuller spanned over more than a decade. In chronological order the relevant documents are: Schuller, 1997a; Fuller, 1997; Schuller, 1998; Fuller, 1998 & 2003; Schuller, 2009.

xxxi For the complexities involved see my “Review of Peter Michel’s Krishnamurti: Love and Freedom“.

xxxii Found in J. Krishnamurti, 1972, Early Talks IV, Bombay: Chetena, p. 100. Second talk at Eddington, Pennsylvania, 14 June 1936. Michel (1997: n139, 193) and I (2010) used the quote.

xxxiii Many of the quotes used in this document were found in Herzberger, 1995.

xxxiv London, 16 Oct 1949, Q7 in The Collected Works of J. Krishnamurti, Vol. 5: p. 354.

xxxv Adyar, 1 Jan 1934, Q2 in The Collected Works of J. Krishnamurti, Vol. 1: p. 172.

xxxvi See Schuller, 2019b, “Theosophy and Krishnamurti: Harmonies and Tensions”.

xxxvii Pulled from different sources by Herzberger, 1995.

xxxviii Johnson, Dominique, 2017.

xxxix See Sender, 2004, “Krishnamurti’s Teachings and Theosophy“.

xl Sanat, 1999: 26, 30-1, 141, 255-70.

xli Idem.

xlii Schuller, 2008a.

xliii Schuller, 2008b.

xliv Meade’s study was written in 1980 therefore did not include the work by K. Paul Johnson (1990, 1994, 1995) and his hypothesis that HPB’s Masters were fictionalized characters based on real-life persons who HPB had met or knew about. How Theosophy might have been cobbled together see Hanegraaff (1998) and Hammer (2004). A good project would be to collect all the studies critical of HPB and the ones responding to those in one bibliography.

xlv. See “The Jaynesian Paradigm and Beyond“. The Schneider & Sagan book is about thermodynamics and entropy and how the evolutionary process could be explained by that basic law of energy behavior. I named their hypothesis the ‘mother of all reductions’ and have an explanatory article titled “Gradiance: The Mother of all Reductions“.