Introduction.

When I read the following passage in a review of a book on the philosophy of music, my understanding of Carnot’s second law of thermodynamics and its philosophical implications kicked in and inspired me to compose an article combining a wide variety of ideas and experiences. This is overdue as I had promised a late friend of mine an explanation of what I meant with the phrase ‘the mother of all reductions’.

According to this [Schopenhauer’s] metaphysics, the world has two aspects: representations and Will, which is the non-rational, aimless force at the heart of human instincts and, indeed, all of existence. Representations are a kind of manifestation of Will. Poetry, painting, sculpture and dance imitate the world of representations. According to Schopenhauer, music is, in contrast, “a copy of the will itself.” The world of representations or phenomena are pale reflections of Platonic forms; the Will is the essence of reality.[10]

What if the aimless, non-rational Will, which Schopenhauer detected at the heart of existence, is nothing but what I would name ‘gradiance‘ (in French accent with a wink to Derrida’s ‘différance‘)? With this I mean the idea that everything exists and changes by the grace of gradient tensions between high and low pressures, high and low densities and high and low temperatures. These are arguably all variations of one phenomenon: uneven energy distribution, which create tensions to be overcome as energy always ‘aims’ at a perfectly evenly dispersed distribution.

Gradiance and Physics

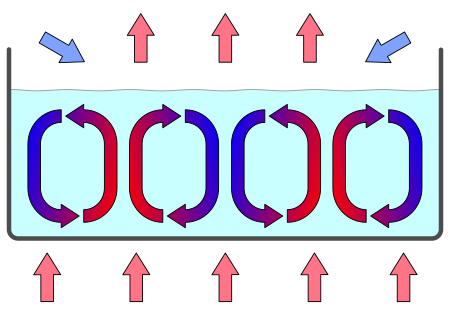

This behavior can be experimentally observed in closed systems and explained with Carnot’s second law of thermodynamics. In physics the final energy state aimed at is called ‘thermodynamic equilibrium’, ‘maximum entropy’ or ‘heat death’. Pessimists might be dismayed by this end point, while optimists will point out that, before the universe will ever die of ‘heat death’, there will be an almost unlimited amount of creative, ordered ways in which this teleological process plays itself out. The Belgian physicist Ilya Prigogine named such emerging orderings dissipative structures [1].

The paradigmatic example of these dynamic structures can be found in the ‘Bénard Cell’ when a fluid in a container is exposed to an increased temperature difference between the bottom plane and the top plane and after a while spontaneously self-organizing, non-linear convection cells form to more efficiently mediate between the gradient temperatures [2].

Convection cells dissipating energy gradients

Convection cells dissipating energy gradients

Gradiance and Evolution

Writer and ecological philosopher Dorion Sagan (son of the famous scientist Carl Sagan) and his co-author Eric Schneider proposed to extrapolate this formative principle of gradiance to any and all phenomena including biological and mental life [3].

Into the Cool: Energy Flow,

Into the Cool: Energy Flow,

Thermodynamics, and Life

He would see our biological life as the thin layer of a very complex energy-mediation system between the cool earth and the hot sun and would see evolution as one of the most inventive tricks in the universe to optimize energy flows. Biological entities are therefore nothing but self-organized energy transformers looking first for high energy sources, then using those sources and lastly leaving lowered energy forms behind.

They are dissipative structures mediating between high and low concentrations of energy. Natural, instinctual desires guide this process at the temporal span of the specious now in which perceptions (‘affordances’ in J.J. Gibson’s terminology) of food, security and procreation are immediately perceived and pursued [11].

Language and mental life–especially narrative constructs which can efficiently hold together multiple dialectical aspects of life–help this process get along as a medium of information storage and exchange of ‘best practices’. This happens at the mediate span of extended temporality of remembered pasts and projected futures accompanied by a temporarily extended sense of narrative self covering one’s life-span [4].

Gradiance and Consciousness

This whole process is also accompanied by different levels of sentience of which our sense of self-conscious self-hood is one of its most intense, especially when fretting over possible courses of action in one’s mind-space while desires and fears have become intensified [5].

Jiddu Krishnamurti

Possibly the most intense experience humans could have is when it can silence its mind through meditation and then experience in this stillness the vastness and intense, whirling energy of the universe itself as was arguably the case with the maverick, global philosopher Jiddu Krishnamurti and his experiences of ‘benediction’. He left us with some poetic descriptions of these experiences, written in a diary he kept for a year in 1961.

[I]t was a movement in complete freedom, a movement that had no direction and dimension; in that movement there was boundless energy whose very essence was stillness. . . . In this emptiness there was fury; the fury of a storm, the fury of exploding universe, the fury of creation which could never have any expression. It was the fury of all life, death and love. But yet it was empty, a vast, boundless emptiness which nothing could ever fill, transform or cover up [6].

When I attended the 1980 Krishnamurti gathering in Saanen, Switzerland, I had just started reading this Notebook, which opened my own mind to similar experiences.

Gradiance and Phenomenology

When talking about consciousness I would also like to make the connection between gradiance and Husserl’s phenomenology, especially the concept of the three-staged process of intentionality [12]. Intentionality here means the feature of directedness of consciousness towards something beyond itself, usually something complex like a landscape, a melody, a text, a social situation, etc.

Husserl makes the case that before we see a rolled-up rope as such, understand a string of words as a text, or hear a string of sounds as a melody, we approach the rope, text or melody initially with an empty intention which projects a possible fulfillment which might come to fruition, or not. The rope might turn out to be a snake, the text turns from a gentle love story into a dystopian nightmare, and the melodic structure sought in the sounds might stay elusive.

A successful fulfillment of an empty intention is achieved when a certain degree of identity can be established. The snake is really a snake because it looks like one, moves like one and reacts like one if you poke it. The end of the story makes the contrary beginning retro-actively meaningful. And the melody, once captured, is clearly repeated throughout the composition and can be reproduced by humming or by a skilled musician.

My proposal is that the dynamic, intentional structure of consciousness can be framed as an instance of gradiance, because there is an initial, teleological tension to be overcome between the empty phase and its fulfillment in possible identity. To be short, intentional experiences of desire and fear are connections between one’s natural evolved instincts projected emptily (like in hunger, thirst and attraction) unto one’s surrounding looking for fulfilment. Experiences of music connect intentionality to higher modes of experience, which will be the focus of the rest of this essay.

Gradiance and Music

How does art, especially music, fit into this discourse? According to the French philosopher Paul Ricoeur fictional narratives are laboratories for alternative ways to see and experience social life [7]. Characters and plots indicate possible templates for one’s own life to better overcome or mediate between all the diverse inner tensions and outer demands to which one is exposed.

Phrasing it in that way connects narrativity of course with managing one’s own energy field of natural desires, social habits and deliberative practices, and the possible ways to improve on them which might lead to different experiences of resolution and satisfaction. Within such a framework the phenomenon of art can be conceived as a very efficient medium to help both individual and collective energy transformations by provocatively breaking up old patterns and establishing new ones.

Bringing in the movie critic Roger Ebert and the sociologist Norbert Elias, one could muse that art functions as an ’empathy machine’ [8], which fuels the jagged civilizational process of increased empathy coupled with increased self-control with sometimes serious set-backs including disintegrations [9].

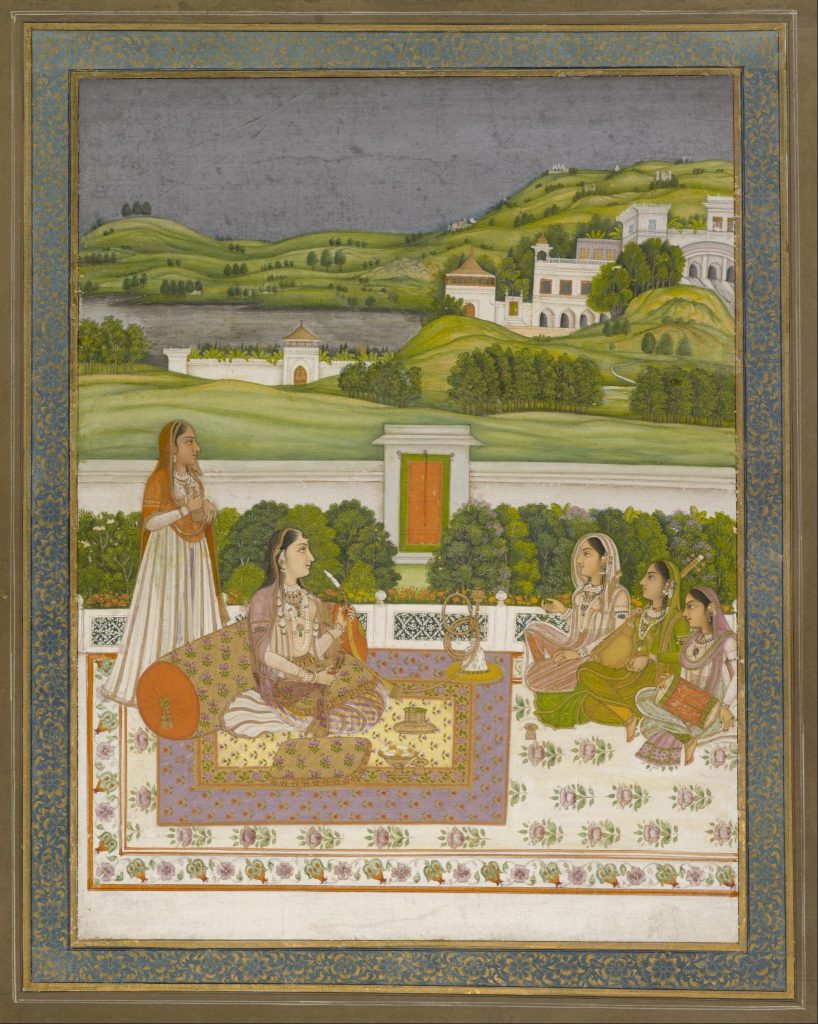

How does music fit in, especially its ineffable and utopian aspects highlighted by philosophers of music? Is music a non-verbal dissipative structure, which, qua experience, can be placed between literary art and meditation, if meditation can be re-conceived not merely as a spiritual practice but as a form of art by itself? Let’s work that out a little, first with connecting music with literature, then with meditation.

As an art-form music is arguably higher than literature because of its more expansive, emotive and energetic ‘meaning’, a meaning which does not refer to anything concrete outside itself but still evokes by its ineffable, spatial-temporally structured experience the depths, tensions, and resolutions of life itself.

To connect music with meditation I would first refer to personal experiences of nature mysticism in which one looks at, or into, nature through freely configurated dynamic gestalts of spontaneously arising perceived patterns in, for example, groupings of rocks and trees and other ‘compositions’. Such meditative way of seeing and being is highly creative and depends on a certain acquired skill of creatively perceiving gestalts and letting go of the usual chatter going on in one’s inner mind-space. In short, it is a form of art.

Secondly I would refer to my experiences of meditation after intensely listening to music, which can open up the appreciation of music’s containment in its silent and empty, spacious background. This background silence becomes foreground when one switches into a silent meditative mode and the lingering of the music becomes the background which then qualifies the particular silence of the foreground.

All such experiences are quite ineffable, but can still be, after reflection, find some words to get expressed by.

What about the ‘utopian’ aspect of music? In the review one can read that the German philosopher Ernst Bloch sees in music the “dialectical confrontation between two contradictory halves: formalism and materiality, rationalization and singular exemplarity, speculative autonomy and embodied immanence” and that “utopia is something that cannot be simply presented, represented, or even indicated; it must be obscurely interpreted through the abstract and translucent tone of the fugato. Music’s ineffability is a perplexing impetus to utopian insight” [10].

Leaving aside whether the above categorial dichotomies, like form vs matter, can be framed as conceptual expressions of an underlying gradiance, I would venture that music, interpreted as a temporally extended dissipative structure, has an intrinsic teleology towards a temporary or ultimate energetic resolution.

And one could, at the collective level, project into such experience of benign resolution, the emotive insight of a state of societal affairs which is commensurate to the music: Equally peaceful and dynamic, or whatever societal preferences one would like to project. In this manner the societal-formative power of music can be understood and shaved of its Romantic and/or esoteric interpretations [14].

Though the above view of interpreting art, music and meditation through thermodynamics looks like a stark, deflationary reductionism, this does certainly not imply a desolate devaluation of such experiences themselves. On the contrary, I see the second law of thermodynamics as the ‘mother of all reductions’ with which one can dismantle all kinds of fancy religious and metaphysical frameworks which will then open a more Taoist or Zen Buddhist sense of embodied, post-cognitive, energetic modes of being sans theological or metaphysical superstructures. And in this manner the Mother of all Reductions can pave the way for the Mother of All Experiences: The mystical experience of gradiance itself as was arguably experienced and expressed by J. Krishnamurti [6].

Endnotes

[1]. Prigogine, Ilya & Stengers, Isabelle. 1984. Order out of Chaos: Man’s New Dialogue with Nature. New York: Bantam Books.

[2]. “Rayleigh–Bénard Convection“. Entry Wikipedia.

[3]. Schneider, Eric D.& Sagan, Dorion. 2005. Into the Cool: Energy Flow, Thermodynamics, and Life. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

[4]. Moore, Chris & Lemmon, Karen (Eds.). 2001. The Self in Time: Developmental Perspectives. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

[5]. Jaynes, Julian. 1976. The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

[6]. Krishnamurti, Jiddu. 1976. Krishnamurti’s Notebook. New York: Harper & Row.

[7]. Ricoeur, Paul. 1983-88. Time and Narrative. 3 Volumes. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

[8]. Ebert, Roger. 2005. “Ebert’s Walk of Fame Remarks”. Roger Ebert’s Journal, 24 June 2005. Retreived 30 May 2020.

[9]. Elias, Norbert. 1978 (1939). The Civilizing Process. Vol 1: The History of Manners. Vol 2: Power and Civility. Jephcott, Edmund (Transl.). New York: Pantheon Books.

[10]. Gallope, Michael. 2017. Deep Refrains: Music, Philosophy, and the Ineffable. Chicago : University of Chicago Press.

[11]. Gibson, J.J. 1986. The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

[12]. Sokolowski, Robert. 1974. Husserlian Meditations: How Words Present Things. Evanston, IL: Northwestern U.P.

[13]. Young, James O. 2018. Review of Michael Gallope, 2017, Deep Refrains: Music, Philosophy, and the Ineffable, Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews, 22 April 2018.

[14]. For two great examples of esoteric interpretations of music see:

Scott, Cyril. 1933. The Influence of Music on History and Morals. London: Rider & Co.

Tame, David. 1984. The Secret Power of Music. Rochester, VT: Destiny Books