Review-essay of Wouter Kusters, Philosophy of Madness: The Experience of Psychotic Thinking, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2022

Govert Schuller

In this article I will aim at giving an overview of Dutch philosopher Wouter Kusters’ phenomenal study, Philosophy of Madness, with some asides about what is phenomenologically important in it.

Kusters’ Philosophy of Madness: The Experience of Psychotic Thinking is a must read for all interested in philosophy, mysticism and madness, and the disturbing closeness, even overlap, of all three, indicated by the following thought-provoking short statements: Philosophy, madness and mysticism all have in common that their point of departure is in the suspension of the ‘natural attitude’ (Husserl), inauthentic average everydayness (Heidegger), or our collective, narrative identity (Ricoeur). They all step out of consensual, common-sense reality. Philosophy and mysticism are modes of controlled madness. Madness is uncontrolled philosophy and mysticism. Madness develops its own philosophy, which is not necessarily mad. Some insights might only be accessible in the mode of madness. Monist philosophies push you to mysticism, which can take a turn into madness when you make too many imaginary connections too fast. Madness could be cured with a better, less verbal and imaginary mode of mysticism. In (very) short, the book is a true cornucopia of well-developed crossings.

Philosophy of Madness

A more structured introduction to this study might be developed by contemplating the subtle nuances implied by its title. This would be a somewhat Heideggerian manner of unpacking a subject matter, especially by looking at the preposition ‘of’ as a so-called ‘double genitive’ indicating that the study is not only a philosophy about madness (of which there are many variants), but also, and maybe more importantly, delves into the practice of philosophy inherent in madness. The leading idea is that people who are considered mad are not lost in confusion and incomprehensible thoughts, but are in their own way grappling deeply with the meaning of life, their situation and their own sense of identity. This is not to say that Kusters is romanticizing or justifying madness, which some have done in the anti-psychiatry movement. His aim is more towards developing an empathetic understanding of the very complex, meaningful, lived experience of madness, which might provide a better basis for the treatment of people suffering from psychotic episodes, while it is also a philosophical reflection on his own life as Kusters had his own experiences of involuntarily venturing twice into that realm.

The structure of a ‘double genitive’, just to bring into play some more hermeneutic phenomenology, was also applied by Heidegger in the title of his 1923 semester, the “hermeneutics of facticity”, having the double meaning of 1) the non-theoretical interpretation of life as lived and 2) the idea that life as lived has the feature of already having-been-interpreted. In other words, the hermeneutics of facticity involves the interpretive exploration of the historical and contextual dimensions of human existence, which requires more than just abstract analysis or theoretical speculation; it necessitates a hermeneutic engagement with the realities of lived experience. At the same time the hermeneutics of facticity involves uncovering the meaning and significance of our factual existence, including our bodily sensations, emotions, relationships, projects, and encounters with the world, which all of them have already been interpreted by our ancestors, parents, teachers, etc., with the caveat that we have the freedom to re-interpret life’s facticities. This notion of an existential-phenomenological hermeneutics of life is neatly captured by the short expression of the “pan-hermeneutic” nature of human life by Heidegger expert Theodore Kisiel (2014).

About Madness

As far as a philosophy about madness is concerned, Kusters is not interested in the proceedings and findings of modern psychiatry with its diagnostic manuals and what Kusters sees as its dominant discourse of looking at madness as something that happens to the brain in terms of neuronal misfirings, hormonal imbalances or chemical interferences, all of which are incapable of addressing how the madman experiences his reality. Fortunately, there exists a long tradition of “phenomenological psychiatry” inspired by the founding fathers of phenomenology like Husserl, Heidegger and Merleau-Ponty, which tries to look from the inside-out at the experienced reality and world of the mad itself.

“This method attempts to understand the seemingly strange world of the mad, including their thoughts and experiences, without judging them in terms of disorders, abnormalities, and deficiencies. Using this approach, it has been observed that it is not only the language of madmen, their way of perceiving the world, and their emotional responses to it that change; a change also occurs in the very depths of their experiential world—in how they experience time, in how their thoughts and perceptions mutually influence each other, and in how closeness and distance relate to each other.”(7)

Descriptive phenomenologies of madness and curative existential psychotherapies have been developed by Merlau-Ponty, Michel Foucault, Thomas Szaz, Ronald Laing, Ludwig Binswanger, Meddard Boss, Viktor Frankl and quite some others, and Kusters can probably be placed in this category. Arguably he moved the investigation a couple of notches further by delving deeper into the experiences of madness themselves.

But, as much as Kusters appreciates phenomenology and uses many of its findings, this attitude is in his view not going far enough, because it stays on the edge and remains in an observational stance, gathering materials to make subtle differentiations and fitting them in the flexible framework of this school. Kusters proposes to go further and dive into madness “to taste its fluid substance, to feel its movements, whether swimming, diving, or drowning” and will do so with the help of what he calls “spiritual psychiatry” which is premised on the idea that madness and genius are closely related and that some or many mad people are actually highly sensitive and gifted crypto- or proto-philosophers who can help us broaden our experiential and philosophical horizons. But even this school (as well as psychoanalysis, which he puts into play) is “reluctant to break through the thin ice of madness”(8). Kusters wants to go deeper into a risky but also “wonderful” deconstruction in which the relationship between philosophy and madness is turned upside-down: “the madman comes to occupy the chair of the philosopher—and the philosopher ends up in the isolation cell”. In this movement in four phases, which are also the main parts of his book, Kusters is courageously on his own.

“In part I, the madman speaks mainly as a madman, as an object of observation, producing data analyzed by the philosopher. In part II he begins to stir; he dons the garments of the mystic, and his delusional writings are upgraded to the level of mysticism, if not philosophical aphorism. In part III, madness, mysticism, and philosophy join in a circle dance, precipitating a whirlwind in each of the four directions. In part IV, madness crystallizes; the madman rises to the surface from the mystical depths of part III; he solidifies into the more familiar forms of paranoia, paradox, and poetry and is now no longer discernible from the philosopher.”(9)

Therefore, besides the double genitive–setting up a dichotomy between a ‘sane’ philosophy about madness and a ‘deviant’ philosophy in madness–one can read the title also as covering the movement of philosophy into madness and its enriching return out of madness with the idea that we can “forge philosophy from madness”, which theme Kusters presents as underlying his book.

“What does the possibility and the existence of madness imply for commonly accepted ideas about humanity and the world? In what sense is philosophy changed or ‘stretched’ when we admit the ‘data’ of the madman’s experience? What is a philosophy of madness?”(11)

Here I like to interpolate–maybe retreating into my own safer philosophical attitude–that, from the stance of phenomenology, the movement and logic of the above questions and their answers as developed in the book, can be construed as an original instantiation of Husserl’s fundamental methodology, i.e. imaginative variation, by which one plays around with the particular structures and dynamics of a given experience by varying them to find its essential and contingent features and make ever more fine-grained differentiations.

What was maybe overlooked by Husserl, but put to good use by Heidegger and Marleau-Ponty, are the insights to be derived from variations of breakdown and dysfunction, like Heidegger’s broken hammer and the unfortunate cases Merleau-Ponty looked into to understand behavior at its most basic moments of constitution.

When a piece of equipment breaks or is missing, this can become the entry point to a reflection on the inter-connected and co-dependent nature of instruments in a specific setting, like a carpenter’s workshop or surgery room. What comes to light especially is the difference between the primordial, tacit, skilful relationship with equipment as ‘ready-to-hand’ when used, and its derivative, theoretical thingness as ‘present-to-hand’ when observed and inspected. Furthermore, the larger context of using equipment can also become more explicit, like the structures of the ‘in-order-to’ and ‘for-the-sake-of-which’ of the work, all together constituting a ‘referential totality’ of a ‘work-world’ of a skilled worker, and beyond it, referring to the world of its intended users and equipment producers, including nature as the source of raw materials (Heidegger, 1961:102-7).

In Kusters’ case this method is pushed into the domain of madness, or the breakdown of consensual normality, not merely taking the madman’s data as a meaningful variant of normal reality construction, but also by experiencing madness itself as best as possible (empathetically, vicariously or even first-hand in hypo- or full mode) in order to deepen our understanding of both normality and its mad deviations, resulting in fascinating and unsettling insights about the contingent and fragile constitution of the world and ourselves.

Beyond Psychiatry: A Phenomenological Approach

In part I, “Cogitating Your Head Off”, Kusters provides a great tableau of such mad experiences and their variations in the realm of the cognition and perception of reality; the experiences of what is ‘outer’ and what is ‘inner’; and the experiences of time and space. He analyzes what can happen to these reality-anchoring categories when they enter the “ocean of madness” and become transformed and fragmented and thereby disrupt regular philosophical discourse and even lays claim to philosophy itself.

A special spot in Part I is reserved for Husserl’s phenomenology of inner time-consciousness, one of the deepest reflections on the possibility conditions of conscious experience, and in Kusters’ writing a tool to understand both normal and psychotic experiences. How do we keep the coherence of consensus reality running in a semi-chaotic flow of events? And what happens when that breaks down and a psychotic manner of meaning-construction takes over? How can we best understand the Husserlian analysis of the interplay between memory, the just-passed (retention), the present, the just-to-come (protention) and expectations in the construction and change of reality? Furthermore, Kusters also reflects on the subject matter of time and its complexities, which itself can become so perplexing that thinking loses its footing and can go into a mad overdrive. This is where the philosopher can slip from controlled, experimental thinking, into hyperreflexive perplexity, possibly resulting in uncontrolled psychotic thinking.

As an illustration of what might happen when a mad experience of time takes over, Kusters provides a few sections narrating his own experiences as he lived them himself (Fragments III & IV). In Part I he shares eight of such fragments of personal experiences, which reminded me of the absurdist science fiction writings of the American author Kurt Vonnegut in the sense that the experience of flow still has the structure of a meaningful, coherent narrative, but then solipsistically personal and for an outsider seen as detached from normal reality. It is in these fragments and the quoted passages from other madmen of mad experiences that the reader can “taste its fluid substance” and “feel its movements” most closely. Again, much can be learned from things going wrong.

Into Mysticism & Madness

In Part II, “Via Mystica Psychotica”, Kusters goes deeper and leaves behind explanatory frameworks and intends to

“analyze what happens to the madman when he no longer has the security of the prosaic, and when fixed identities, images, words, and thoughts all melt, dissolve, and disappear. In this part, the emphasis is more on the mad process than on the mad condition. The kind of madness to be discussed here is what outsiders are more likely to call manic . . “(163)

And a new important mode of experience is inserted into the analysis and that is mysticism in order to help to further the analysis of philosophy and madness by finding parallels and communalities between madness and mysticism. The focus is on four subsets of phenomena where things can go wrong and each deserved a chapter: the perception and experience of truth (Detachment); the use of images and the imagination (Demagination); the problems of expression and language (Delanguization); and the transformation of the process of thinking (Dethinking). Some of the leading questions are about the difference between mad hallucinations and mystic visions and why some uncommon experiences lead to serenity and others to madness. The core of his musing seems to be the following train of thought, though he thinks it not entirely adequate.

“Perhaps the mad experience is a logical continuation of the mystical experience. The madman carries on with the journey, while the mystic drops out prematurely. For the very reason that he is connected to a tradition that has prepared him for his experience, the mystic will hold fast to certain assurances, identities, or traditional distinctions–such as the difference between good and evil–and that makes him incapable of penetrating the most extreme domains. The madman goes further and deeper, but he also pays a higher price: many do not return from this transmarginal zone–or so this line of reasoning goes.”(171)

Even though considered inadequate and maybe too romantic, this question seems to be one of the book’s core dilemmas in evaluating the respective value of a) controlled mysticism embedded in a tradition and b) manic mysticism which has broken through all conventionality and continues to explore “the realm of paradoxes, paranoia and prophetic madness”(171).

Mystical Delusions in Four Variations

After this analysis of the commonalities and differences between madness and mysticism, philosophy is again put to use in the analyses in Part III, “Light Mists”. Here Kusters differentiates more ethereal and abstract categories in “mystical madness”, which are “the One, being, infinity and nothingness”(280). Each again deserved its own chapter, which titles indicate we are dealing here with a set of fascinating and overlapping delusions which delineate the essence of mystic and manic experiences.

The chapter on the “uni-delusion” is framed by Plotinus and his mystical concept of the One, which is the apex of a hierarchical structure comprising everything, i.e. “all dimensions of life and the cosmos”, which will appeal to all people with a monist inclination. The problem, as Kusters sees it, is that aiming at experiencing the One leads to a mode of spiritual interiorization which leaves the body behind.

“The One is everywhere and nowhere; it’s a lovely idea for the mind, but for the body of the uni-deluded individual, it means nothing but fragmentation and alienation. If my mind is swallowed up in the One, my body is swallowed up in general scattered physicality.”(297)

Being: Immersion in sensory ecstasy, detached from others

The “esse-delusion” addressed in chapter 10, seems to aim at the opposite of the “uni-delusion” in that it is more exterior. Here Kusters, among a few, uses the drug-induced experiences of the British author Aldous Huxley to make his points that the “esse-delusion” is more experiential, aesthetic and focused on visual-sensory perceptions, which induce a sense of intense being, even “too much being”(320). In this analysis Kusters also addresses the mystical aspects of music, both in its capacity to induce mystic experiences, but also to soothe the minds of the mad. The problem here is that a new mode of “subjectification” emerges, one which leaves behind our fellow subjects by becoming too wrapped up in one’s solipsistic ecstasy and avoiding others.

As an aside, I would point out that Huxley’s work on mystical ecstasies set within a this-worldly, sensory here-and-now might have been deeply influenced by his friendship with the global sage Jiddu Krishnamurti, who arguably was promoting a form of quiet, non-cognitive, post-egoic nature mysticism and also had a deep appreciation of music. In this regard see Huxley’s foreword to Krishnamurti’s first book published by a major publisher (Huxley, 1953).

The third delusion, the infinity-delusion, I will treat separately in the next section as it is the start of a phenomenological contemplation on the role of the imagination in both sane sense-making and its mad variant.

Nothingness: Hyper-reflexivity leading to existential emptiness

The fourth delusion, the nothing-delusion in chapter 12, is the logical outcome of the process of the “de-xx-ing” on the via mystica psychotica, which destroys all mental content in the course of becoming “thoroughly detached, demagined, delanguized, and dethought”(389). Everything is questioned in a heightened state of reflexivity to the point where the normal relationship between being and nothingness is flipped. Where being used to be the norm and nothingness an aberration, in the experience of the psychotic the tables are turned and a hyperreflexive doubt undermines any and all tacit, common sense understanding of being and the resulting abysmal emptiness becomes the norm.

“Ordinary human reflexivity is stripped from the ground of existence and becomes a raging, nihilistic, inhuman hyperreflexivity in the vacuousness of Ø.”(396; with Ø standing for nothingness)

And a little further:

“… the mystical madman “slips away” from being by doubting everything, by calling everything into question, and by subjecting the most ordinary things to the scrutiny of a questioning and burning hyperreflexivity. This leads to perplexity that can be understood as the question mark with a capital letter, as the state of questioning in which there is no longer a questioned or a questioner, and as total nothingness: Ø. When being is swallowed up in questioning, the mystical madman disappears into nothingness. Hyperreflexivity is like the whirlpool that leads to an infinitesimal point of concentration in the endlessly vast, bottomless ocean of being.”(399)

For phenomenologists, Kusters’ analysis of the thoughts on nothingness by Sartre and Heidegger will be of interest. In the case of Sartre, the idea of the linkage of madness and the Husserlian concept of time is brought back. For Sartre human time is only possible if and when a break is inserted between the past and the future, a break by ‘nothingness’ in order to free man from its past and be open to its future, and this will be accompanied by anguish if we are conscious of it. And the presence of other people has a role in this constitution of freedom in anguish. Therefore, the structure of consciousness includes nothingness, being and others in an interdependent manner. In madness this structure also falls apart. In the Ø-delusion, nothingness swallows up being, others are left aside, and with them morality too, and the mood can waver between demonic and cheerful.

“Ø functions as the drain through which all possible life is carried away, sooner or later, in the sewer of nothingness.”(411)

Kusters calls Heidegger one of the “optimistic nothingness experts”(424), who recommends anxious encounters with nothingness, especially for philosophers, in pursuing the question of why there are beings rather than nothing. And it is fine if the grounds of one’s being disappear and you become speechless. This pursuit is harmless as long as you are not drawn into the realm of the imaginary with its illusions and hallucinations. It is all controlled and benign. But in mystical madness a more terrifying question is posed: “Is there anything at all? Isn’t there actually absolutely nothing?”(426) Here again might be the fine line between controlled philosophy and being in the runaway grip of madness.

The chapter ends with a discussion of the soteriological concepts of nothingness in the “nihil-centric”, spiritual philosophies in the east and their overlap with some aspects of the Ø-delusion. Kusters consulted the work of religion scholar Mircea Eliade on the “via mystica orientalis” of the yogi. Both yogi and madman turn their back to reality, including other humans and even their own body, and find it all illusory, and both become entangled in another, opposite world of detachment and emptiness, the yogi in samadhi or sacred nothingness, and the madman in the Ø-delusion. And again, their difference might lie in their measure of control, though the factor of cultural acceptability has to be taken into account. By western standards a yogi might get locked up and by eastern standards a madman might be venerated.

Rock Bottom

Part IV, “Crystral Fever”, dives into the end point of philosophy, mysticism and madness, that is complete disintegration in perplexity, solipsism, chronic psychosis, mania and paranoia. But here I will leave the summary and plunge into a contemplation on the role of the imagination in madness.

The Hidden Productivity of the Transcendental Imagination

Both mysticism and madness transgress all limits and touch thereby an ineffable infinite. Mathematical philosophy joins the two when it tries to think through what it means “to keep on counting” and asks where it ever might stop. In the chapter on the infinity-delusion Kusters starts with a discussion of the many infinities the German mathematical genius Georg Cantor could generate, including the ultimate infinity of infinities, the one he identified with God. Besides the obvious idea that infinities are mental concepts, Cantor thought infinities were somehow also to be found in reality. Many of his peers thought he had gone maybe too far into some form of pantheism. Kusters thinks that Cantor, who struggled with mental health issues, might have been the first to get trapped in an infinity-delusion.

Infinity in Reality

Kusters’ grappled with a similar ontological claim by Rudy Rucker, that “mathematical infinity can be found in reality”(335). How that could be interpreted, is the starting point for me to bring in a cluster of ideas with which I struggled when I wrote my MA dissertation on narrative identity and the role of the faculty of productive imagination.

I will first summarize Kuster’s processing of Rucker’s claims, then present my phenomenological ideas derived from Heidegger’s phenomenological interpretation of Kant regarding knowledge and action, after which I will present my own re-arrangement of these ideas and apply them to madness.

Rucker’s example of a ‘real’ infinity is the infinite length of the English coast encompassing a finite amount of land. The more you zoom into a stretch of coast, the more its irregularities add to the length of the coastline “until the measuring instrument breaks down and you slip into the realm of the molecular and the atomic”(339). The other, similar example is the phenomenon of fractals in which irregular lines or surfaces multiply seemingly without end into ever more detailed and longer lines when you zoom in.

But, Kusters questions this alleged experience of infinity and asks himself if this infinity is only taking place in your mind and whether you see only pixels “onto which you are projecting infinity?” Kuster then states that “Infinity is located somewhere between mind and matter, between thought and perception”, or maybe even beyond these faculties. Mathematicians therefore only “imagine” or “conceptualize” infinity “on the inside of his eyelids.”(340)

The Fregean and Kantian Distinctions

When contemplating these conundrums, I was thrown back to the dizzying complex of ideas in Heidegger’s phenomenological interpretation of Kant’s epistemology, but also the intuitively simpler Fregean differentiation between the sense (Sinn) and the reference (Bedeutung) of a word or expression. Both provide some possible clarification to Kusters’ questions, and by extension, to the issues he addresses in the overlap between madness and philosophy.(Frege, 1960)

In the framework of Frege the word ‘infinity’ can have a sense or meaning, but not necessarily a reference or experience. You can think the concept infinity and combine it with a lot of meaningful predicates, but its reference is always beyond one’s thought and perception. And maybe in Kantian terms, and like his concept of noumenon, one can think the concept infinity, but never experience it. Whatever you might experience is only phenomenal. And if you think you have the real thing, it is only an image seen with the mind’s eye.

The segue into Heidegger’s Kant is this little concept ‘image’ and the pivotal role it played in the A edition of Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason, which addresses the question how the understanding (concepts) and intuition (experiences) are linked in order to produce empirical knowledge. Kant’s question was how concepts, which by themselves are empty, could be applied to experiences, which by themselves are under-organized (except for spatial and temporal aspects), and, other way around, how experiences could be subsumed under concepts.

In the A edition Kant elaborated on the “transcendental faculty of the productive imagination” as the necessary mediator between concepts and perceptions. What this faculty does–going from concepts to perceptions—is to generate from the concept a series of rules inherent in the concept, from which a series of images can be generated, which might then connect with a series of perceptions. Or, again other way around, this faculty can derive from our semi-chaotic experience a set of images, which can be formalized into patterns, which can be connected to the rules inhering in a specific concept.

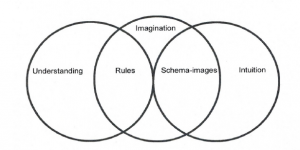

Fig. 1. Kantian mandala of the three major faculties

Kant provides the examples of a dog and a triangle to indicate the steps of how concepts can be made more sensible and intuitions more intelligible.

Heidegger’s Phenomenological Expansion

Kant dropped these insights in the B Edition and Heidegger later thought that was a mistake, because Kant’s work on the imagination in its role of producing knowledge had a profound congruence with the basic structure of phenomenological intentionality. What Heidegger brought into position was the tri-partite dynamics of the intentional structure of meaningful experiences, one of the breakthrough insights developed by Husserl (Heidegger, 1962b & 1997).

In a static, structural sense, phenomenological intentionality is always already of the form that consciousness is consciousness-of-X, and the dynamic aspect is that most experiences, if not all, start with a) emptily intending ‘X’, which pre-experiential, meaningful structure might then b) get fulfilled in an experience, after which c) the identity between the projection and its fulfilment is intended. So, we can emptily mean ‘dog’, then see a dog and then experience that the meaning and the seeing are congruent and the concept dog is applicable.

What Heidegger did, was to overlay the dynamic structure of intentionality onto the dynamics engaged in by Kant’s imagination, such that the imagination is the faculty which can emptily project structures (rules and images), which then can connect with intuitions, which, after their identity is established, is stable enough to affirm or connect with a concept. In this way there is a congruence between:

Kant : Imagination Intuition Understanding

Husserl : Empty intending Fulfilment Identity / conceptualization

This insight by Heidegger of lining up Kant’s faculties with Husserl’s intentionality was a tremendous help in deepening my understanding of all three big philosophers involved, including also Ricoeur, whose work on narrative identity and the complex synthesis of emplotment explicitly referred back to Kant’s faculty of the productive imagination as the enabling factor of our more or less fictitious sense of life-span identity.(Ricoeur, 1983: 68 & 1985: 3)

Surprisingly also Heidegger seemed to have dropped these ideas as he moved from phenomenology to a more poetic thinking, though one insightful Heidegger scholar made the case that Kant’s concept of the imagination and Husserl’s concept of empty intentionality did survive in Heidegger’s existential concept of Dasein’s projective possibilities as an integral part of our manner of being-in-the-world.(Richardson, 2004: 153f)

Imagination, Madness, and Creativity

This processing of Heidegger’s phenomenologized Kant also led to an epiphany, which also gave me great help in understanding the role of the projective imagination in the act of philosophizing itself and its intensification and possible derailment in madness.

My rearrangement of Heidegger’s Kant is premised on the idea that the imagination can not only provide a measure of freedom from reality-perception in purely mental endeavors like fiction, fantasies, hypothesis-formation, and running provisional scenarios in one’s ‘inner mind space’, but also provide a creative freedom in engaging in the perception-action cycle relatively free from ideations, like in dance, children’s play, mindless routines, sports and sexuality.

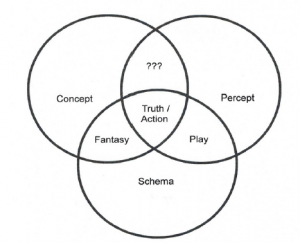

In the following figure the term ‘schema’ replaced ‘imagination’ and a third field of possible experiences and actions is indicated with Truth / Action, in which all three faculties work together

The re-arranged figure looks like this:

Fig. 2. Simple Three-ring Mandala

In the Truth and Action category one can place all experiences to which all three faculties contribute. Staying with Kant and the early Heidegger, the idea is that truth is a product of the harmonious cooperation of all three faculties. Truth is traditionally conceived as located in a proposition as its truth value, but in phenomenology the concept of truth increasingly shifted towards perception and, in the hands of Heidegger, became identified with the ‘opening’ enabled by the projective faculty of imagination. Following the German-American political philosopher Hannah Arendt, the arguably highest level of action (communal and political) would necessarily bring in the understanding because such action is mostly executed by speech and legislative acts in which conceptual entities like ideals, plans and promises are brought to verbal expression.(Arendt, 1958)

In all three fields of a) inner-mind fantasy, b) enacted play or c) complex truth / action scenarios, we can proceed conventionally and obey the explicit and tacit rules of one’s society; or proceed creatively in a post-conventional manner without getting in trouble; or engage in the mad variations of all three in either a) one’s mind with seemingly delusional ideations; or b) in public with seemingly incomprehensible play-acting; or c) with interventions in other people’s lives or the political arena based on seemingly inappropriate truth claims and proposals.

A Reframed Model of the Imagination

The main point here in connecting this phenomenological framework with madness is that maybe this framework might contribute to a better, or at least different, philosophical understanding of madness in its rootedness in the faculty of the imagination, but then with a deeper understanding of the imagination in its role as the transcendental, a priori enabler of any meaningful endeavor whatsoever, be it fantasy, play, intellectual action, or any of its runaway derangements.

A last thought on the conceptualization of mysticism. All three fields have their own mysticism and some might line up with Kusters’ fourfold differentiation of mystical delusions. In the fantasy field it is the emptying of the mind in Zazen, i.e. a sitting meditation disconnected from perceptual reality in which one tries to empty one’s inner mind space without necessarily deconstructing this space itself. It is a going inside, without necessarily challenging the constituted nature of this inside (aiming at nothingness). In the play field one could put the meditation of mindfulness while slowly moving one’s body and being aware of one’s surroundings (aiming at being). In the action / truth field one could find Heidegger’s mysticism of simple daily life experienced within a poetic opening of being-there. And maybe also Krishnamurti’s call for a post-egoic and non-conceptual way of life might fit in this category (aiming at oneness).

Conclusion

Kusters’ Philosophy of Madness challenges us to rethink madness as more than a pathology to be contained and treated. Instead, it presents madness as a complex and meaningful mode of existence with profound philosophical implications. By drawing parallels with philosophy and mysticism Kusters not only illuminates the fragility of normalcy but also the potential richness of what lies hidden in the psychotic thoughts of the madman.

The exploration of the transcendental faculty of imagination and its capacity to construct meaning, can add to the discussion, presenting a framework where the modes of experience in fantasy, play, and truth/action—and the manner in which all three have quotidian, mystical and mad variations—provide another categorization of human experiences in their complexity.

Ultimately, Philosophy of Madness is a call to embrace the unsettling questions posed by madness as illuminating contributions to understanding ourselves and the world. Kusters invites us to see madness not as a deviation but as a thought-provoking byway of the philosophical journey—a journey that, while risky and not to be recommended, holds the promise of profound insight and possible healing.

Wouter Kusters (PhD) studied linguistics and philosophy, and is an independent scholar and teacher in the Netherlands. He wrote two prize winning books on philosophy and madness in Dutch, and the last one – A Philosophy of Madness: The Experience of Psychotic Thinking – has been translated into English (2021) and Arabic (2023), while a Chinese translation is due to appear this year. His most recent book’s title is in English: Shock Effects: Philosophizing in the Age of Climate Change (2023). For more information, readers can visit his website at: https://kusterstekst.nl/.

Source

This review-essay of Philosophy of Madness was published in the Indian journal, Cetana: A Journal of Philosophy, 5/1 (Jan 2025): 38-58.

Cetana is published by the Centre for Phenomenological Studies.

Sources

Arendt, Hannah. 1958. The Human Condition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Binswanger, Ludwig 1963. Being-in-the-World: Selected Papers of Ludwig Binswanger. Translated by Jacob Needleman. New York: Harper & Row.

—–, —–. 1993. Dream and Existence. Co-authored with Medard Boss, edited by Michel Foucault, and translated by Keith Hoeller. London: Humanities Press.

Boss, Medard 1963. Psychoanalysis and Daseinsanalysis. Translated by Ludwig Binswanger. New York: Harper & Row.

—–, —–. 1965. A Psychiatrist Discovers India. New York: Grune & Stratton.

—–, —–. 1979. Existential Foundations of Medicine and Psychology. Translated by Stephen Conway and Herbert Wehner. Lanham, MD: Jason Aronson.

Foucault, Michel 1965. Madness and Civilization: A History of Insanity in the Age of Reason. Translated by Richard Howard. New York: Vintage Books.

—–, —–. 1973. The Birth of the Clinic: An Archaeology of Medical Perception. Translated by A.M. Sheridan. New York: Vintage Books.

—–, —–. 2006. Psychiatric Power: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1973–1974. Translated by Graham Burchell. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Frankl, Viktor E. 1946. Man’s Search for Meaning. Translated by Ilse Lasch. New York: Beacon Press.

—–, —–. 1955. The Doctor and the Soul: From Psychotherapy to Logotherapy. Translated by Richard and Clara Winston. New York: Vintage Books.

—–, —–. 2000. Man’s Search for Ultimate Meaning. New York: Basic Books.

Frege, Gottlob. 1960. “On Sense and Reference”. In: Translations from the Philosophical Writings of Gottlob Frege, P. Geach and M. Black (eds and trans), Oxford: Blackwell, 56-78.

Geniusas, Saulius. 2015. “Between Phenomenology and Hermeneutics: Paul Ricoeur’s Philosophy of Imagination”. Human Studies, 38/2: 223-241.

—–, —–. 2018. “Productive Imagination and the Cassirer-Heidegger Disputation”. In: Geniusas, Saulius & Nikulin, Dmitri (Eds), 2018. Productive Imagination: Its History, Meaning and Significance, London: Rowman & Littlefield International, pp 135-156.

—–, —–. (Ed). 2018. Stretching the Limits of Productive Imagination: Studies in Kantianism, Phenomenology and Hermeneutics. London: Rowman & Littlefield International.

—–, —–. & Nikulin, Dmitri (Eds). 2018. Productive Imagination: Its History, Meaning and Significance. London: Rowman & Littlefield International.

Heidegger, Martin. 1962a. Being and Time. Macquerrie, John & Robinson, Edward (Transl). New York: Harper Collins.

—— . 1962b. Kant and the Problem of Metaphysics. Churchill, James (Transl). Bloomington, IN: Indiana U.P.

—— . 1985. History of the Concept of Time: Prolegomena. Kisiel, Theodore (Transl). Bloomington, IN: Indiana U.P.

—— . 1997 (1977). Phenomenological Interpretation of Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason. Emad, Parvis & Maly, Kenneth (Transl.). Bloomington, IN: Indiana U.P.

Husserl, Edmund. 1964. The Phenomenology of Internal Time-Consciousness. Churchill, James S (Transl). Bloomington: Indiana U.P.

Huxley, Aldous. 1954. “Foreword”. In Krishnamurti, Jiddu, The First and Last Freedom, New York: Harper & Brothers.

Jaynes, Julian. 1976. The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Johnson, Mark. 1987. The Body in the Mind: The Bodily Basis of Meaning, Imagination, and Reason. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Kant, Immanuel. 1978. Critique of Pure Reason. Kemp Smith, Norman (Transl). London: Macmillan.

—— . 1987. Critique of Judgment. Pluhar, Werner S (Transl). Indianapolis, IN: Hackett Publishing.

Kisiel, Theodore. 2014. “The Paradigm Shifts of Hermeneutic Phenomenology: From Breakthrough to the Meaning-Giving Source”. Gatherings: The Heidegger Circle Annual, 4: 1-13.

Krishnamurti, Jiddu. 1954. The First and Last Freedom. New York: Harper & Brothers.

Kusters, Wouter. 2022. Philosophy of Madness: The Experience of Psychotic Thinking. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Laing, R.D. 1960. The Divided Self: An Existential Study in Sanity and Madness. London: Penguin Books.

—–, —–. 1964. Sanity, Madness and the Family. Co-authored with Aaron Esterson. London: Penguin Books.

McVeigh, Brian. 2024. The Self-Healing Mind: Harnessing the Active Ingredients of Psychotherapy. New York: Oxford UP.

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice 1942. The Structure of Behavior. Translated by Alden L. Fisher. New York: Beacon Press.

—–, —–. 1945. Phenomenology of Perception. Translated by Donald A. Landes. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Richardson, William. 2004 (1963). Heidegger: Through Phenomenology to Thought. Fourth Edition. New York: Fordham U.P.

Ricoeur, Paul. 1978. “The Metaphorical Process as Cognition, Imagination, and Feeling”. Critical Inquiry, 5/1: 143-159.

—–, —–. 1979. “The Function of Fiction in Shaping Reality”. Man and World, 12/2: 123– 141.

—–, —–. 1983-88. Time and Narrative. Vols. 1-3. Chicago & London: University of Chicago Press.

—–, —–. 1992. Oneself as Another. Chicago & London: University of Chicago Press.

Schuller, Govert. 2019. The Possibility Conditions of Narrative Identity. Dissertation; Masters in Research in European Philosophy; Dr. Adrian Davis, Research Supervisor; University of Wales, Trinity Saint David, Lampeter, Wales, UK.

Szasz, Thomas 1961. The Myth of Mental Illness: Foundations of a Theory of Personal Conduct. New York: Harper Perennial.

—–, —–. 1970. The Manufacture of Madness: A Comparative Study of the Inquisition and the Mental Health Movement. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press.

—–, —–. 1988. Schizophrenia: The Sacred Symbol of Psychiatry. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press.