The leading questions of this presentation are: How do Theosophy and Krishnamurti perceive each other? How are their teachings related? Based on primary sources and notes from discussions, I will present a wide spectrum of possible answers as a contribution to an ongoing discussion.

CONTENT

Introduction

Theosophical Perceptions on Krishnamurti

Perceptions of World Teacher Project with K

Perceptions of K’s teachings

Krishnamurti on Theosophy and the Theosophical Society

Comparison between Theosophy and Krishnamurti

Dealing with the Differences

Further lines of investigation

Conclusion

Bibliography

Endnotes

=========

Introduction

What I intend to do in this presentation is to develop certain matrices or certain structural insights into a spectrum of possibilities of how a very complex subject can be made more transparent. I do have my personal views on the subject matter, but I will try to keep them out, though that is not always possible. For clarity’s sake, I will follow five major lines of investigation.

The first one is about the possible Theosophical perceptions of the metaphysical status of Krishnamurti. What kind of person was he that he went around the world giving very profound insights? Where did he come from, what is his background?

The next part will be about the possible Theosophical perceptions of Krishnamurti’s teachings. How can we evaluate them, how are they connected with Theosophy, how can we get a grip on that complex subject?

The third part is not about the Theosophical perceptions of Krishnamurti, but Krishnamurti’s perceptions of Theosophy and the Theosophical Society, which are of course historically connected.

The fourth part will be a comparison between Theosophy and Krishnamurti on certain very specific subjects.

The fifth and last part will be an overview of the many ways that I have encountered, and have also experimented with, in how to deal with these differences. Sometimes the differences are big or very enigmatic or puzzling to the point of even disturbing.

The article will finish with an overview of possible further investigations of K as a person and his teachings.

To dispel the fears from people who are very sympathetic to Krishnamurti and who might think that this is a completely wasted exercise, Krishnamurti himself said in 1932 “to find out whether I agree with theosophy or not, you will have to study what theosophy teaches and what I say and examine them impersonally”.i With that guidance we will do that. But again, this is more giving pointers for your own research than that I would like you to attain certain conclusions. Therefore this exercise falls under the second object of the Theosophical Society, which is “to encourage the comparative study of religion, philosophy and science”.

Let us start with a bare-bones background information about Theosophy and Krishnamurti.

The Theosophical Society

Helena Blavatsky and Henry Steel Olcott founded the Theosophical Society in 1875. Its stated aims were and still are:

1. To form a nucleus of the Universal Brotherhood of Humanity, without distinction of race, creed, sex, caste or color.

2. To encourage the study of comparative religion, philosophy and science.

3. To investigate unexplained laws of Nature and the powers latent in man.ii

In addition it can be argued that the aims or the agenda of the Theosophical Society were the following few:

One is to disseminate the doctrines of Theosophy. This is a basic overview of what I think that it is. Our lives are a part of a spiritually evolutionary scheme. We incarnate many times to learn the lessons of life and to evolve into selfless loving, understanding beings. Karma is the great law of cause and effect ordering this evolutionary process and giving us feedback on where we stand. As there are different levels of attainment in this process there are some enlightened souls ahead of us. Here I am referring to the existence of so-called enlightened beings named variously as Mahatmas, Masters, and Elder Brothers. These Masters are the guardians of a primordial Wisdom Religion or Wisdom Tradition. And this is one of the core aspects of Theosophy. This Wisdom Religion is very old, had been developed by these Masters, by Adepts and others with occult skills. This Wisdom Religion is by itself the essence and origin of all other religions and philosophies and sciences. Collectively, these Masters are sometimes called the Hierarchy or the White Lodge and at regular intervals they will send emissaries, they will sponsor deserving individuals and, for our story very important, they will prepare the way for a great spiritual teacher with the aim to re-instruct mankind about its high calling.

Another point on their agenda was to promote the cultural and intellectual revival of India and also its political independence from the British Empire.

The last point on the agenda of the Theosophical Society was to prepare for the coming of a “torchbearer of truth” or Avatar or World Teacher. Blavatsky at the close of her life, in her classic The Key to Theosophy, announced the coming of this “torchbearer of truth” for the later part of the 20th century. The mission of the Theosophical Society, according to Blavatsky, was to prepare the way for this new leader.

He will find the minds of men prepared for his message, a language ready for him in which to clothe the new truths he brings, an organization awaiting his arrival, which would remove the merely material mechanical obstacles and difficulties from his path.iii

Then she painted the possibility of a glorious, long-term goal of this plan and wrote that “if the theosophical society survives and lives true to its mission . . . earth will be a heaven in the twenty-first century”. We are now about a decade into that century. And this is the good thing of having a certain temporal distance to the subject to evaluate.

Krishnamurti

Krishnamurti was the son of a Theosophist who lived close by the international headquarter of the Theosophical Society in Adyar, India. The clairvoyant Charles Webster Leadbeater found him in 1909. Leadbeater noticed the teenager and saw a very selfless, spiritual aura and thought he was a very special young teenager. Leadbeater and Annie Besant were in those days the leaders of the Theosophical Society and Leadbeater, allegedly, was in contact with the Masters. And he was then allegedly informed by the Masters that he had to prepare this teenager as the possible vehicle for a very advanced other Master, the Lord Maitreya.

The plan was that Maitreya–as he had done 2000 years before with Jesus according to Leadbeater–that he would overshadow Krishnamurti, and that both having their consciousness blended in a very intimate spiritual cooperation would bring out a new teaching to humanity. The plan was to do this again, but then with this teenager Krishnamurti as the vehicle. I named this plan the World Teacher Project, because that term was used a lot, though the plan was also very often referred to as the Second Coming because of its connection with Jesus Christ. In 1911 the Order of the Star in the East was founded around Krishnamurti and the Project. Interestingly, and this goes back to the prophecy by Blavatsky, when Annie Besant was challenged about her involvement with this organization by other Theosophists who might have thought the Project was not genuine or it was not proper for her to get involved with it, she defended herself by referring explicitly to the view which Blavatsky had about the future mission of the Theosophical Society. Annie Besant said: “My crime is that I share it, and do what my poor powers permit in preparing the minds of men for that coming”.iv The only difference between her and Blavatsky is that Blavatsky put that event in the later part of the 20th century and Besant advanced that agenda by half a century. Because of the distance in time we can see who might be right. Besant actually said: “Which of us is right only time can show.”

Anyway, everything goes relatively well with the Project and Krishnamurti comes under the tutelage of a Master named Kuthumi. And he gets initiated into the White Lodge, which means that there is an inner occult connection being made between Krishnamurti and the Master so they can be on speaking terms. The high point of the Project was in the period between 1925 and 1927, when Krishnamurti was many times overshadowed by Maitreya. This claim was according to himself and according to some other clairvoyants like Leadbeater and Geoffrey Hodson, who wrote some beautiful descriptions of those occurrences.v But somehow in 1927, Krishnamurti starts having doubts about the Project. These doubts built up to such an extent that in 1929 he decides to go his own way, dissolves the Order of the Star of the East, and distances himself quite radically from Theosophy and the Theosophical Society. He then went solo and kept on meeting, teaching and talking to people for the rest of his. In his now famous 1929 speech when he dissolved the Order of the Star, he formulated his basic spiritual philosophy.

I maintain that truth is a pathless land and that you cannot approach it by any path whatsoever, by any religion, by any sect. Truth being limitless, unconditioned, unapproachable by any path whatsoever cannot be organized, nor should any organizations be formed to lead to or coerce people along any particular path.vi

This is the base line of his philosophy, which he expounded upon in many variations for the rest of his life.

The big question for many Theosophists was: How far away did Krishnamurti go from Theosophy? Here we wade into the issue of the many ways K was perceived by Theosophists.

Theosophical perceptions of Krishnamurti

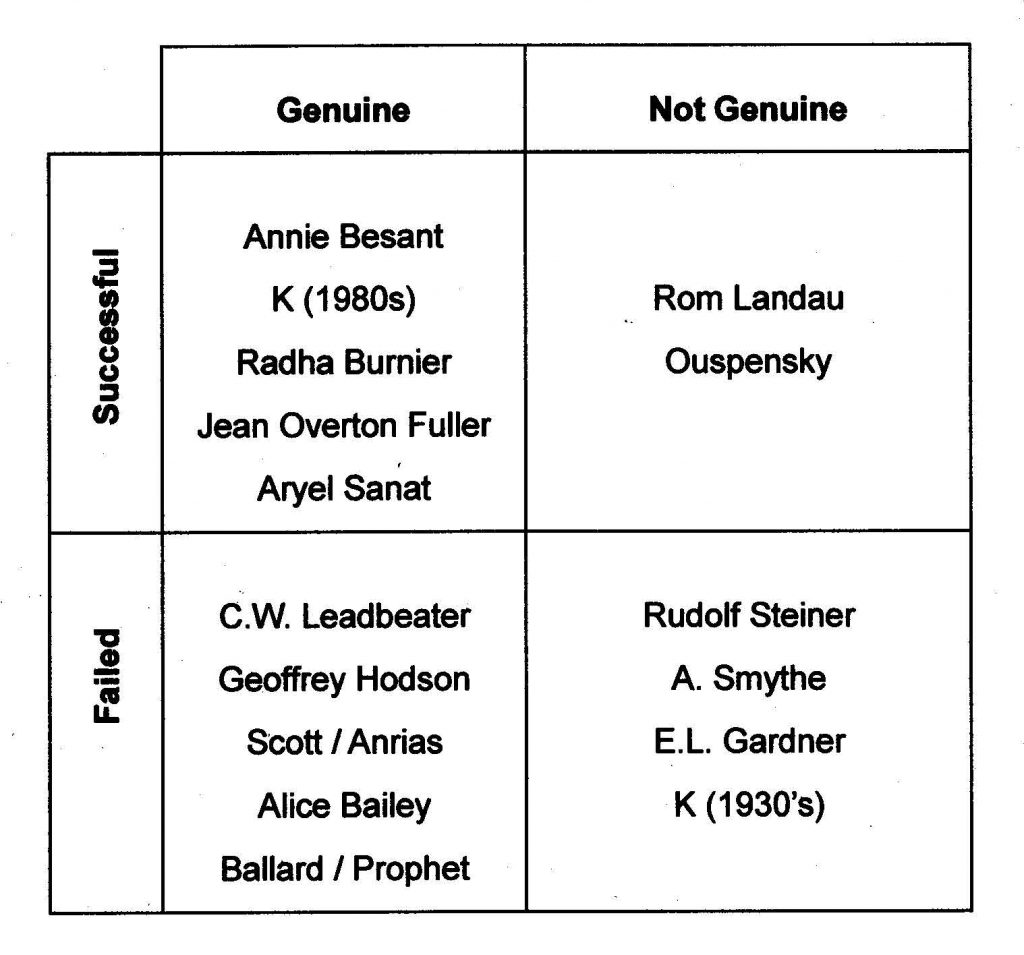

I did some serious research on this and my basic thesis was that–given all the different Theosophical thoughts on Krishnamurti–that all these views can be differentiated according to how people answer two basic questions about Krishnamurti: vii

1. Was the project genuine or not?

2. Was the outcome of the project successful or not?

The possible answers to these two questions generated the four following positions:

1) The project was perceived as genuine and successful;

2) The project was perceived as genuine, but failed;

3) The project was perceived as not genuine and failed (of course); and

4) The project was perceived as not genuine, but succeeded!

And for all the four possible positions there were Theosophists or allied thinkers taking the different positions. The most important among them I discussed in my paper, but here they are placed in their proper quadrant:

of the World Teacher Project

1. The project was perceived as genuine and successful

In the first quadrant we find Annie Besant, Krishnamurti, Radha Burnier, Jane Overton-Fuller and Ariel Sannat. Some quotes from these people will provide an idea of what their thinking was.

Annie Besant was reported to say in 1928 that “The Lord has spoken. I am now satisfied. This is the beginning of all that I have foreseen and worked for”.

Radha Burnier, who is the current president of the Theosophical Society, wrote in 1986 that the Theosophists “were not ready to listen to a profound message” coming from Krishnamurti. And she explicitly compares the situation between Krishnamurti and the Theosophical Society as similar to the Jews and Christ and the Hindus and Buddha. The Jews did not accept Christ. They did not understand him and couldn’t follow him. The same with the Hindus, when Buddha came around. They just didn’t get it. So, in the same way, the Theosophists just didn’t get it. It was a genuine project. Here you have a new World Teacher, but they just didn’t get it.

Jane Overton-Fuller is a Theosophical scholar and wrote some really interesting books. Her position was that Leadbeater and Besant were basically right with finding Krishnamurti, but everything else they did, they were wrong. It was not necessary to build up an organization around Krishnamurti; that, because it was the Second Coming, he would have apostles; and that there would be a church. There were a lot of things around the Project which were peripheral, and according to Jean Overton-Fuller most of it was wrong and unnecessary. And because how everything happened, it became understandable that eventually Krishnamurti had to distance himself from all that buildup and that he had to disassociate himself from the Theosophical Society.

Many years later K himself reinforced this view. In 1980 he said “the boy was found, conditioning took no hold–neither the Theosophy, nor the adulation, nor the World Teacher, the property, the enormous sums of money–none of it affected him.” Apparently he is saying that he came into Theosophy, breezed out of it and nothing kept him there. Problem with this is that it can be refuted by his own words from the earlier days. In those days, and I’m talking about 1909 when he was found and 1925 when the Project came to its fulfillment, it is very clear that he was a convinced Theosophist. He would lecture eloquently about the basic ideas of Theosophy. And that was not just for show, or because he was coerced to do that, or because it was expected from him. If you read these reports, the impression is that it came from really deep down and was very authentic. So there is something not jiving with his later view and his earlier view.

What did he otherwise think about himself as a World Teacher? In 1931, he wrote to someone very close to him “You know, mum, I have never denied it, I have only said it does not matter who or what I am but that they should examine what I say which does not mean that I have denied being the W.T.” So there is some admittance and he seems to say: “I’m the guy, but that’s not important. Forget about it; forget about my status. What I say, that’s important.” Something similar can be found in his book Truth and Actuality when he discussed with some people in England the subject of the upcoming biography of his life by Mary Lutyens. Much of his history would come out into the open in a well-researched book and much information would be new to people who were into Krishnamurti or even new for Theosophists. In these talks he is reported as saying

There is a very ancient tradition about the Bodhisattva that there is a state of consciousness, let me put it that way, which is the essence of compassion. And when the world is in chaos that essence of compassion manifests itself. That is the whole idea behind the Avatar and the Bodhisattva. And there are various gradations, initiations, various Masters and so on… viii

Of course this is a part of a larger quote, and if you read the whole quote it is quite clear that he is referring to himself. But in a way he used to do very much later, he would talk about – he would speak but he would not refer to himself in the first person, but in the third person and say “the speaker.” But he then clearly is referring to himself in an objectifying way. The point is that if you get used to that, you can interpret the quotes as referring to himself.

2. The project was genuine but failed.

First Leadbeater. What he thought was initially not easy to find out, because Leadbeater had an understanding with Annie Besant that he would not contradict whatever she would say in public. And as Annie Besant took the position ‘here is the World Teacher Krishnamurti; the Project is fulfilled’, Leadbeater would not say anything contrary to that. But, privately, we now know–and this came out in the 1960s–he had a different point of view. In 1930 he stated in an article

This is He who should come, and there is no need to look elsewhere; as I have said, I know that the World-Teacher often speaks through Krishnaji.

Here he backed up Annie Besant. But in private we now know he said, “The Coming had gone wrong”.

The second person in this box is Geoffrey Hodson, the other clairvoyant Theosophist next to Leadbeater. As I just referred to, by clairvoyant seeing, Hodson gave a beautiful description of the overshadowing of Krishnamurti by Lord Maitreya. Later Hodson believed the Project had failed and for three reasons. First of all Krishnamurti had a hard time dealing with the spiritual energies that were going through him. There was something going on in him that is called the “rising kundalini energies”. It was a part of his preparation, but it was very painful. In the period between 1921 and 1927 he had many weeklong periods experiencing excruciating pains, even to the point that he would faint. According to Hodson his body might have been too frail for these enormous energies to deal with.

Another reason that Hodson thought Krishnamurti did not fulfill his plan was the death of Krishnamurti’s brother Nityananda in 1925. These two brothers were very close. Nityananda developed a very grave health condition. Krishnamurti is said to have asked the Masters a request to spare his brother’s life. He thought that the request would be fulfilled. When his brother actually died, he was absolutely devastated. This is a frequently proposed reason why Krishnamurti had a change of heart. Hodson also said that Krishnamurti was very hurt by what other Theosophists did and say. There were some little scandals and strange episodes in the 1920s. They were so bizarre that Krishnamurti did not want to have anything to do with them. One issue was the announcement in the summer of 1925 by Annie Besant that there would be twelve apostles connected to his mission as a World Teacher. Krishnamurti had no appetite for that. He didn’t see that that would be genuine or necessary and he felt very uncomfortable being put in that position of people expecting a whole “Jesus show” including apostles. Anyway, all this contributed to Krishnamurti’s “decision to withdraw from the role that might have been his”. And this quote is from Hodson.

At this point I like to address the views of the British composer and Theosophist Cyril Scott. Because there are many quotes ascribed to certain Masters in this story I like to present such quotes in a neutral format so you can decide for yourself about the source and its veracity. The formula I will use is: “Master X per y in source z”. For example “Master Kuthumi said per Krishnamurti in At the Feet of the Masters” or “Master El Morya stated per Mrs. Prophet in The Chelah and the Path”. I am adopting this format because I want to suspend the question of the reality of the Masters as I am reporting them here and also bracket the truth of their pronouncements. I like to keep that neutral. It is up to ourselves to establish if these sources are legitimate or not.

Anyway, Scott wrote anonymously in the early 1930s the book The Initiate in the Dark Cycle, which contains two elaborate chapters dedicated to Krishnamurti. The book reads like a novel because it is written in a conversational style. Its main characters are the protagonist and his spiritual teacher Justin Moreward Haig. Interestingly there are people looking for who this person really was, because all the characters in the book are presented as real life characters. We do know who certain persons were and there is something of a sub-culture of Theosophists and non-Theosophists looking for Justin Moreward Haig.1 Then there is also a character named “Sir Thomas” presented as a full-fledged English Master. During an after dinner conversation ‘Sir Thomas’ stated that the project with Krishnamurti was a “success while still overshadowed by the World-Teacher, . . . a failure afterwards”.

The most sustained effort to identify the characters was done in Fuller, 1998. One of the real-life characters speculated to be one of Scott’s Initiates in his The Initiate in the New World book was Dr. Pierre Bernard, who ran an ashram in Nyack, New York. Scott visited the ashram on his US tour. Bernard and the happenings at his place were colorful and influential enough to deserve his own biography. See Love, 2010.

Teaming up with Scott in the 1030s was his friend, the British astrologer and Theosophist Brian Ross, who wrote under the pseudonym David Anrias. He also was allegedly connected with the Masters and in 1932 published the book Through the Eyes of the Masters with nine messages from different Masters accompanied by pencil drawings of them. Maitreya was one of these Masters and he stated through Anrias that because Krishnamurti had taken initiations along the line of the Deva-evolutions “it became all but impossible for him to be used any longer as my medium”.ix So Maitreya was saying that Krishnamurti took a specific initiation, therefore could not be used as his vehicle anymore, and therefore the the Project had to be called off.

Alice Bailey was also a Theosophist and prolific author. She was allegedly in communication with a Master called Djwal Kul. Djwal Kul per Alice Bailey in Discipleship in the New Age said that the Project was experimental and for various reasons “… the experiment was brought to an end.”

The last one in this list is Elizabeth Clair Prophet, leader of the American New Age organization The Summit Lighthouse. Here we meet Kuthumi again, who was allegedly Krishnamurti’s own former guru. He stated in 1975 per Mrs. Prophet in “An Exposé of False Teachings” that Krishnamurti was “selected to take the training for the calling of representing the World Teachers and the coming Buddha, Lord Maitreya,” but he “failed the test of the intellect and of the subtleties of spiritual pride”.x In short, it was a genuine Project but it failed because of K’s psychological shortcomings.

3) The project was perceived as not genuine and failed (of course)

There were a lot of Theosophists who said that the Project from the beginning was not genuine. From an historical point of view, one of the most important ones was the German clairvoyant and author Rudolph Steiner. His position is an interesting one because it involves spiritual geopolitics. According to Steiner impostor Masters had hijacked the Theosophical Society and used Besant, Leadbeater and Krishnamurti as unwitting instruments in a occult power game directed against humanity in general and the West in particular. The founding of the Anthroposophical Society by Steiner was a direct consequence of the view he had about Krishnamurti. When the Order of the Star was founded in 1911, the Council of the German Section of the Theosophical Society, of which Steiner was then general secretary, declared that no one could be simultaneously a member of the Order of the Star and the German TS. You had to choose, you couldn’t be member of both organizations. This went against the official policy of the Theosophical Society. If you want to be a member of anything else, the Theosophical Society cannot tell you what to do there. The logical reaction from the TS headquarters in India was to revoke the charter of the German section. Though that happened in 1913, Steiner had already in 1912 founded his own Anthroposophical Society and brought most of the German Theosophists with him in that big split off.

Another person that did not think it was all genuine was Mr. Albert E.S. Smythe, a well-regarded Canadian Theosophist. He denounced the Project and called it an “extraordinary delusion” and “absolutely contrary” to the literature of the Theosophical Society of Blavatsky’s days. And this ties into a discussion that a lot of what Leadbeater and Besant were bringing out as Theosophy was seen by other Theosophists as not in accordance with what Blavatsky was saying. They called it neo-Theosophy or even pseudo-Theosophy.

Edward Gardner, an influential English Theosophist, came out in 1963 with quite a controversial view. Gregory Tillett, Leadbeater’s biographer, said the following about his idea:

Leadbeater unconsciously created an entire artificial system, based upon his own strongly held views, and, again unconsciously, used his own occult power to vitalize this system into a state where it had the appearance of reality, and appeared as an objective reality to him when he viewed it clairvoyantly. xi

That is a fascinating thought. So, Leadbeater’s conversations with the Masters, his clairvoyant witnessing of initiations and whatever else was experienced by him as genuine, was nothing but a stage unconsciously created by himself. This is something for psychologists to look into and see if there are other examples of this kind of self-deception.

4) The project was perceived as not genuine, but succeeded!

Now we arrive at the interesting part where there are some people saying that the Project was successful but it had no genuine starting point at all.

This comes from Rom Landau, a writer on spiritual subjects who traveled in the 1930s interviewing people like Steiner and Krishnamurti. He heard the allegation that the Project was a bold invention. Make a person believe he will be a messiah, create a mass movement around the idea, and maybe it will come to fruition. How about that, not? Just a little mass manipulation. Rom Landau wrote that “it appears that Leadbeater and Annie Besant believed to the very end that Krishnamurti was thus developing naturally into the personality of the `World Teacher'”.xii So, if great lies can justify great ends, that is wonderful.

Theosophical perceptions of the status of Krishnamurti’s teachings

The next big part after addressing the Theosophical perceptions of Krishnamurti as a World Teacher is to look at the perceptions of the status of Krishnamurti’s teachings. First suggested by someone we will talk about, I came up with this structure of the perceptions of the relationship of Krishnamurti and Theosophy. in four variations.

of the Teachings of Krishnamurti and Theosophy

K & T stand for Krishnamurti and Theosophy and the circles represent their teachings. If K and T are in the same circle this means their essence is very close and if in different circles their essence is not close. How much the circles overlap indicates the extent to which they agree. The matrix is determined by two basic questions. Do K and T share the same essential teachings? And how much overlap is there on secondary issues? This generated the following possibilities:

1. Essentially the same, and hardly diverging on secondary issues.

2. Essentially the same, but diverging on secondary issues.

3. Essentially different, but overlapping on secondary issues.

4. Essentially different, and without any overlap.

Essentially the Same or the ‘K teaches Theosophy Hypothesis’

I found nobody taking position 1, but it is a possibility. Somebody might come up with it and might say “You don’t get it, they are the same essentially.” This would amount to saying that what Krishnamurti is teaching is part and parcel of Theosophy and would name this the K teaches Theosophy Hypothesis.

Only Diverging on Secondary Issues or the Revisionist Hypothesis

At position 2 we have TS presidents Annie Besant and Radha Burnier taking the position that, though their teachings are essentially the same, they do diverge on many secondary issues.

Before addressing that, I want to get back to Hans and Radhika Herzberger. Both are Krishnamurti scholars and edited a very useful paper titled “Krishnamurti on Theosophy: A collection of reference materials”. te paper was online for a while on the Krishnamurti Foundation web site, but has now been withdrawn. They name position 2 the Revisionist Hypothesis and think it was held by certain Theosophists who would make the claim that, despite the quite radical anti-Theosophical statements by Krishnamurti, there is still this very intimate connection between the two.

Revisionists hold that, while he may have disagreed with Theosophy on certain issues, he continued to teach its ‘central’ doctrines.xiii

So, we have Radha Burnier and Annie Besant in that position. To be more precise, Annie Besant’s position on Krishnamurti’s teachings and work is as follows:

Say, if you like, that we are two sides of one work. Dr. Besant is at the head of one side and Krishnaji of the other. One is the work of the Manu, the other the work of the Bodhisattva.xiv

The Manu is another important Master in the Theosophical pantheon with a certain role in occult and spiritual affairs. Interestingly, in 1949, Krishnamurti had a response to this idea.

You may deceive yourself by saying, “What you say and what I believe are the same. They’re the two sides of the coin”. You may say what you like, but that is mere self-deception.xv

So, K is blocking the possibility that there would be something essential in common. He is actually more radical than that and I will share later on some quotes to that effect. Radha Burnier said that

To every ancient truth found in cryptic form in the teachings of the religions of the world, he gave a new dimension.xvi

Here we have to interpret “ancient truth” as meaning Theosophy, being a repository of ancient truths. And in that way the sentence would read: “To every Theosophical truth Krishnamurti gave a new expression.” In short, teaching-wise they are essentially the same, but K gave it a new expression.

Only Overlapping on Secondary Issues or the Deviation Hypothesis

Following Herzberger’s lead, I propose to call position 3, the Deviation Hypothesis. Deviationists would hold that while Krishnamurti deviated from the essential teachings of Theosophy, there is still overlap. Geoffrey Hodson can be seen as taking that position. According to Hodson the teachings of Krishnamurti were

. . . an extraordinary blend of rare flashes of transcendental wisdom, penetrating intelligence, incomprehensibility, prejudice, intolerance and vituperation.xvii

And he gave many an examples and expressed how he felt. He was a very convinced Theosophist who said at a certain moment “we are getting beaten up here by Krishnamurti by what he is saying about Theosophy and it’s time to say something back.” Most Theosophists seemed to be a bit numb in the 1930s about what Krishnamurti was saying. Hodson was one of the rare ones coming out saying “hey, the guy is going a little bit too far, we have to give a little bit of push back here.” About 25 years later he expressed a milder view. He said that the

. . . the splendid teachings, verbal and written, demonstrate that he is indeed, in his own right, an advanced Soul with an aspiring message to deliver to mankind.xviii

Hodson was a very nice person and was not someone who wanted to kick up too much dust and be controversial. In another statement from 1939, he said “everything which is comprehensible and rings true in Krishnamurti’s utterances is recognizable as part of the Ancient Wisdom.” Here again you have to read Ancient Wisdom as Theosophy. He is saying that there are a lot of things Krishnamurti is saying, which are true and are in accord with Theosophy and the Ancient Wisdom. At the same time Hodson said that there is plenty that is not.

Another elaborate expression of this position, where there is overlap but no essential coming together, comes through Cyril Scott. This time it is his teacher, Justin M. Haig, who stated

. . . instead of giving forth the new Teaching so badly needed, he [Krishnamurti] escaped from the responsibilities of his office as prophet and teacher by reverting to a past incarnation, and an ancient philosophy.xix

Haig then stated that Krishnamurti is teaching a variant of the Advaita, monist version of Vedanta philosophy. If you know Vedanta, and Shankaracharia is the great philosopher in Vedanta, you will find a lot of congruencies between what Krishnamurti is saying and what Vedanta is saying. To this, added ‘Sir Thomas’, that Adviata Vedanta is a “philosophy for chelas, and one of the most easily misunderstood paths to Liberation”.xx And that might be because it is a very complex, subtle and deep philosophy, which can be easily misinterpreted in a simplistic way.

There is some interesting research to be done about these statements. For example, the reincarnation referred to is maybe the one according to Leadbeater in which Krishnamurti was a disciple of Aryasanga, a Buddhist teacher and the founder of the Yogacarya school and identified by Leadbeater as a former incarnation of Master Djwal-kul.xxi Leadbeater, with his clairvoyant capacities, investigated 48 lives of Krishnamurti, which were published in 1925 as The lives of Alcyone, and this live as a Buddhist scholar was number forty-seven.xxii But the ancient philosophy referred to, you would expect that to be a form of Buddhism that Krishnamurti fell back into, because he was in that incarnation a Buddhist scholar. But the ancient philosophy, according to Scott’s characters, is Adviata Vedanta, a major school in Hindu philosophy. Though this might not add up entirely, according to Blavatsky

The Vedanta system is but transcendental or so to say spiritualized Buddhism, while the latter is rational or even radical Vedantism.xxiii

This same point she makes at different places, i.e. that at a deeper esoteric level the deepest teachings within Hinduism and Buddhism are the same. In that way it might add up, Krishnamurti had an incarnation as a Buddhist scholar, but then fell back in his last life into a Hindu philosophy.

Back to Scott’s friend Anrias again. The following is quite a quote, which goes to the essence where Krishnamurti and Theosophy differ. It is Maitreya per Anrias in Through the Eyes of the Masters:

Thus although Krishnamurti was right to emphasize the necessity for independent thought, he was wrong in assuming that everyone else, regardless of past Karma and present limitations, could instantly reach that point which he himself had only reached through lives of effort, and by the aid of those Cosmic Forces apportioned to him solely for his office as Herald of the New Age.xxiv

The big question with Krishnamurti is that he presents a spiritual view in which he asks people to go through an instantaneous, non-methodical transformation. In K’s kind of Enlightenment, there is no method to it and there is no guru to help you in that process. Nothing, it is instantaneous. On the other side you have Theosophy saying that this is a regular process, which takes quite a while and you have to work at it. There are rules involved, initiations etc. What Maitreya is pointing out is that Krishnamurti is making a mistake. Krishnamurti achieved a certain level of spiritual attainment and then says everybody can get up there, just like that. And he has an issue with that.

Essentially Different without Overlap or the ‘Total Split Hypothesis’

And now we get to, and this was a surprise, to box number 4, which is the position that both are essentially different and without any overlap. Again I want to follow Herzberger because he suggested this kind of structural organization. I will call this the Total Split Hypothesis. This hypothesis holds that Krishnamurti and Theosophy hold nothing in common and therefore there is no overlap. And if there is any overlap, it is insignificant. I found two persons holding this position: Krishnamurti himself and allegedly his former guru, Master Kuthumi.

For example Krishnamurti stated in1935 that “I am not a Theosophist nor a Theosophical missionary”xxv and in 1949 “What I say is diametrically opposite to your beliefs”. xxvi And at a Theosophical convention at the headquarters of the Theosophical Society in Adyar to which he was invited to speak he said:

Sirs, these two things are wholly different: what you are thinking and doing, and what I am talking and doing. The two cannot combine. Your whole system is based on exploitation, on following authority, on belief and faith.xxvii

This is quite clear and strong language. And there are many more similar quotes that you might find in this paper by Herzberger or scattered throughout K’s Collected Works.

The other person we find in this position is Elizabeth Clare Prophet or allegedly Master Kuthumi who stated per Mrs. Prophet in one of the series of Pearls of Wisdom in 1975 the following:

Today Krishnamurti, denounced by the Brotherhood, denounces the true teachers and the path of initiation, proclaiming that the individual needs only himself and that this is the only God there is. Leading thousands of youth in the direction of sophisticated disobedience to the God within, to Christ the inner mentor, and to the masters of the Brotherhood, this fallen one has been the instrument of a philosophy that is not and does not in any way represent the true teachings of the Great White Brotherhood.xxviii

This quote posits quite clearly the incompatibility of K’s teachings with Theosophy and is covered therefore, like K’s own position, by the Total Split Hypothesis. And the split duplicates the earlier mentioned agreement of Maitreya per Anrias and K himself about their incompatibility as far as K’s metaphysical status is concerned.

In finishing this overview I would like to repeat my position regarding the veracity of these quotes. I am merely reporting what can be found in print. And I am neutral regarding the ontological status of these Masters and the status of the veracity of their words. Figuring out those questions is all up your own research and thinking.

Krishnamurti on Theosophy and the Theosophical Society

Let us continue with the third big block, Krishnamurti on Theosophy and the Theosophical Society. Here I let him do most of the speaking, because it is quite clear what he is saying. There is a best case and a worst case quote from him, so we have a nice contrast. These are medium long quotes. Best case, he is talking here to Theosophists:

If you are really a social body, not a religious body, not an ethical body, then there is some hope for it in the world. If you are really a body of people who are discovering, not who have found, if you are a body of people who are giving information, not giving spiritual distinctions, if you are a body of people that have a really open platform, not for me or for someone special, if you are a body of people among whom there are neither leaders nor followers, then there is some hope. . . .

Don’t you see, if you really thought about these things and were honest, you could be an extraordinarily useful body in the world. You could then really work for the intrinsic merit of its ideas – not for some fantasy and emotionalism of your leaders. Then you would examine any idea, and find out its true significance and work it out, and not depend on the honors conferred for your services, on the enticement to work.

But, here comes the but:

But I am afraid you are followers, and therefore you all have leaders. And such a society, whether it is this or another, is useless. You are merely followers or merely leaders. In true spirituality there is no distinction of the teacher and the pupil, of the man who has knowledge and the man who has not.xxix

Now, we go to the worst case. These all come in a question and answer format from between 1929 and 1936.

Q: How can you say spiritual societies are a hindrance to man’s understanding? Or does this not apply to the Theosophical Society?

JK: [Every society which] stands on any authority, whether of the Buddha, Christ, or the Masters, has no significance. It merely becomes the means of exploiting people through their fears.xxx

Another good question, well not a good question actually, because people knew the answer actually, I think:

Q: Are you or are you not a member of the Theosophical Society?

JK: I do not belong to any religion, for organized belief is a great impediment, dividing man against man and destroying his intelligence. These societies and religions are fundamentally based on vested interests and exploitation.xxxi

That I thought was the worst-case statement by K on the Theosophical Society and any other spiritual society. To round this off there are two short quotes on the teachings of Theosophy itself.

Q: I have studied Theosophy very deeply and . . . I say that your wisdom is essentially the truth of Theosophy.

JK: You may study profoundly all the Theosophical books, but your conception of wisdom is utterly false. You gather dust from books and call it wisdom. I speak of a natural wisdom, beyond all books. To me your theories are utterly valueless.xxxii

Or in 1934, he said, as quoted before:

Sirs, these two things are wholly different: what you are thinking and doing, and what I am talking and doing. The two cannot combine. Your whole system is based on exploitation, on following authority, on belief and faith.

So far on Krishnamurti and Theosophy.

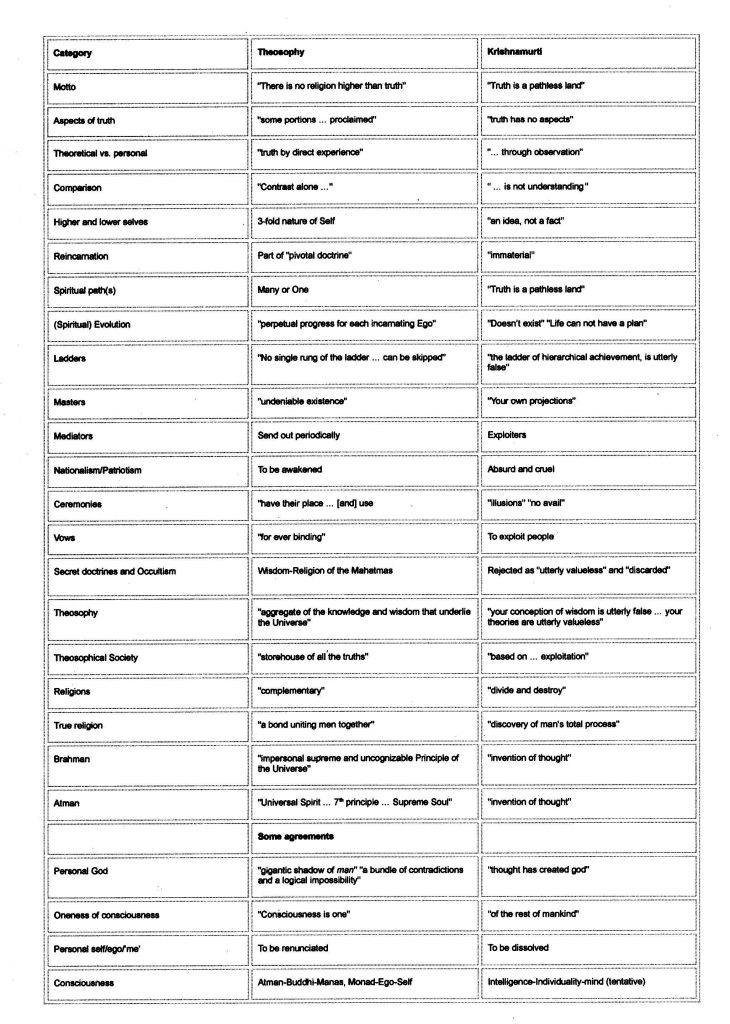

Comparison between Theosophy and Krishnamurti

I would like to direct your attention to the triple column comparison. The first column is the subject matter, the second contains what Theosophy would say about it, and the third is what Krishnamurti would say. Many of these categories were suggested by the aforementioned paper “Krishnamurti on Theosophy” by the Herzbergers, who looked into the conversions or diversions between the two, though they did not present it in this manner. In this way we can find out if there is overlap or not. The footnoted version you can find here. And I put them on-line so you can do research for yourself and see if these quotes are taken out of context or otherwise inappropriately used. Of course, there is also the question about what in their respective teachings is essential and what is not. Problem with that is that there might be different definitions of what is essential in Krishnamurti and what is essential in Theosophy. Nevertheless, we can go through some of these.

(A clearer on-line version here)

The fourth one is right away interesting because it is about comparison itself and therefore addresses the methodology followed itself. What Blavatsky is saying about comparing, and I have a quote here from Blavatsky. And this is a quote, which I have found many times as the heading on a certain article.

Contrast alone can enable us to appreciate things at their right value, and unless a judge compares notes and hears both sides he can hardly come to a correct conclusion.xxxiii

Opposite this pro-comparison statement from Blavatsky is Krishnamurti saying that comparison is not understanding. If you compare two items, you destroy both. You have to see one item for what it is and you have to see the other item for what it is, but if you start comparing, everything is lost. In that sense, he says again, it is competition. Because that is based on comparison. There is a way where you can differentiate where he would allow comparison because say in science you have to make comparisons. He would not object against that. So there are ways that thought can use comparison in legitimate ways. Although Krishnamurti is very often making very generalized statements about something. So, you might think that well, any comparison is out of the question, dangerous, don’t do it, stay away from it. But you can make differentiations, where, for example, where he is taking many examples he is taking is that people compare themselves where they are. Either socially or financially or psychologically, or whatever. If you start comparing that is something destructive. Because that breeds competition, that breeds fear, fear breeds conflict and there you go down the path into trouble.

Anyway, there are some subjects about which it is very clear what Krishnamurti and Theosophy are thinking.

Higher and lower selves. Theosophy is positing that there is a three fold nature of the self. Actually at the bottom comparison you will see, in all the teachings from Blavatsky it is called the Atman, Buddhi, Manas. Leadbeater called it the monad, ego and the self. Krishnamurti said such ideas are merely that, just idea, not facts, so forget about it.

Reincarnation. This idea is a pivotal doctrine of Theosophy, but for Krishnamurti it is immaterial.

Spiritual paths. It is not completely clear what Theosophy might say about it. There might be many or there is only one. For Krishnamurti “Truth is a pathless land” and there is no Way you can get there. There are no paths to, from or in that ‘space’.

Spiritual evolution. This is a core concept in Theosophy, being the perpetual progress for each incarnating ego. We keep going and going until we get off the ladder of reincarnation and then there is even more evolving to do. Krishnamurti states that spiritual evolution doesn’t exist, that life cannot have a plan. The thing about ladders is that it implies a gradual process. “No single rung of the ladder can be skipped” says Blavatsky, while Krishnamurti counters with the idea that the ladder of hierarchical achievement is utterly false.

Masters. For Theosophists they have an undeniable existence and a lot of them will testify to that, even Krishnamurti himself. You can go back to his own writings in the period between 1911 and 1929 where he reports on his interactions with the Masters. But the later Krishnamurti says that they are products of your own projections.

Mediators. According to Theosophy spiritual emissaries are sent out periodically and Krishnamurti was meant to be one of them. K said they are all exploiters.

Nationalism / patriotism. This is a sensitive matter for many. For many Theosophists the sentiment is positive and to be awakened, like ones love for family and community. This idea has to be seen also in the context of Theosophists contributing to India’s struggle for cultural and political independence. Early Theosophists promoted the idea of Indians becoming more loving of their own religions, culture and country and not become weighted down by a negative self-image put upon them by the British Imperialists. For Krishnamurti nationalism is an absurd and cruel obstacle to world unity and used by exploiters for their own ends.

Ceremonies. They “have their place, they have their use” and should be respected “for the sake of those good souls to whom they are still important”. This quote came from Krishnamurti’s At the Feet of the Master, which was allegedly dictated by his former teacher Kuthumi (or was written by Leadbeater), so I put it in on the side of Theosophy. For the later Krishnamurti ceremonies are illusions and “to no avail”.

Religions. In Theosophy they are complimentary. All religions carry an aspect of truth; they all blend altogether; and they originate from the same transcendental source. Krishnamurti states quite clear and repeatedly that they divide and destroy.

Brahman and Atman. Brahman is the impersonal, supreme and un-cognizable principle of the universe. For Krishnamurti the concept is an invention of thought, which also applies to the concept of Atman.

Now we arrive at some agreements, and those are interesting. And if you think that these points of agreement are the essential teachings of both Krishnamurti and Theosophy, then you are in that position where Theosophy and Krishnamurti are basically the same.

Personal God. He is a “gigantic shadow of man”, a bundle of contradictions and a logical impossibility. Krishnamurti more or less agrees: Thought has created God.

The oneness of consciousness. This is an important issue. Theosophy is saying that consciousness is one, i.e. that our experience in daily life of being separate individuals is in the last analysis an illusion. We are all one, or we are all aspects of something which is larger than ourselves and we all are an integral part of that. The experience of separateness is illusory. Krishnamurti has the same idea. “Consciousness is the consciousness of the rest of mankind”, he states. Your consciousness is mankind’s consciousness. We are all going through the same thing. We do not know where we are and we are all groping for a way out. We are all in the same boat, but not as individuals, but as one undivided movement. There’s no inside, there’s no outside, there’s no me, there’s no you, and there is even no my ego and there is no your ego.

The personal self, the ego, the me. And still, somehow there is a way out. And the way out might be very similar in Theosophy and K, even an essential part in both teachings. In Theosophy the ego is to be renunciated and we are encouraged to engage in a self-less life in service to mankind. For Krishnamurti, the ego has to be dissolved through a transformative insight of the mind into itself.

Differentiation within consciousness. The last topic is still tentatively in the process of development. The case could be made that there is a congruence between the Theosophical trinity of Atman – Buddhi – Manas and Krishnamurti’s concepts of intelligence – individuality – mind. This calls for a creative, interpretive reading of Krishnamurti’s basic terms, but it is feasible. Atman is the divine self which, because it can be equated with Brahman, is a transpersonal force which can manifest in one’s life. In a parallel manner K thinks that intelligence is something far beyond the personal mind, but can act upon it. Buddhi would be your higher self in which resides a sense of individuality. Krishnamurti defines individuality as a person who is whole, who is non-divided. He says we are in a state of being divided, we are in inner conflict, and this state can be overcome. And there is Manas, which is the thinking part in Theosophical psychology. It is very clear in Krishnamurti’s teaching that intelligence can work on the mind if the process is not interfered with by the ego, or the ‘me’. Inspired thinking is possible. One could also add the parallel between Theosophy’s notion of Kama-Manas (literally the desire-mind or ‘everyday self’) and K’s notion of ego. In short, one could argue for a parallel between a set of basic terms.

Dealing with the Differences

Now we are coming to the last part of this article, that is, how are we dealing with the differences?

Again, and wonderfully so, the Herzbergers come up with the Convergence Theory, which claims that all the criticisms lobbed at Theosophy by Krishnamurti have been taken serious and incorporated. I would counter that that position is stretching it. But it is a hypothesis and can be tested against the evidence. The evidence he finds is in two examples: The disappearance of both nationalism and ceremonies from Theosophy. There is something to that observation but it is a long way to say that Krishnamurti’s criticisms of Theosophy have now been disarmed by relevant changes in Theosophical doctrines and practices.

On the other side, why not have an alternate Convergence Theory? And I can think of two. Alternate convergence theory # 1: The previous theory is a one-way transformation of changing Theosophy and the Theosophical Society in such a way that it would be acceptable to Krishnamurti and to what he is teaching. But how about the other way around? How about we interpret Krishnamurti’s teachings within an esoteric framework as developed by Theosophy and making certain corrections here and there. For example what I tried to do in the Consciousness category above comes down to a creative playing around with Krishnamurti’s teachings such that you will find some congruence. Such a strategy is quite legitimate and actually the study by Hodson titled Krishnamurti and the Search for Light can be seen as an attempt towards that end. If you read it you will find it is a fair reinterpretation of what Krishnamurti is saying about Theosophy.

Now there is an alternate convergence theory # 2. This is basically coming from Aryel Sanat, who in 1999 published the book The Inner Life of Krishnamurti. He is reinterpreting all the mystical, esoteric aspects of Krishnamurti’s life in such a way that the distance between Krishnamurti and Theosophy is drastically diminished. He focuses on Krishnamurti’s clairvoyant experiences, his mystical experiences, the so-called Process of the kundalini, and K’s use of language. A lot of facts are now in the public domain about Krishnamurti’s hidden, esoteric life, which form and content any Theosophist will understand.

So, you can restructure Krishnamurti’s life as being completely understandable in Theosophical terms. Sanat, I think, goes a little bit far in this reconstruction. For example, one of his assertions is that Krishnamurti had a “lifelong relationship with the Masters and the Lord Maitreya”xxxiv and the way he uses evidence for that is problematic to say the least. His book needs a very critical reading, because it contains many interesting but also problematic parts.

Another way to deal with this difference between Krishnamurti and Theosophy is to see it as a part of a so-called Hegelian dialectic. Hegel, a great philosopher of the early 19th century, developed the idea of dialectics. It is the process of thesis, antithesis and synthesis. Theosophy would be the thesis: Masters, initiations, gradual development, occult powers and manifestations, etc. This system was bound to attract an antithesis. And that came with Krishnamurti: no Masters, no initiations, revolutionary one time transformation etc.

Now the logic of dialectic will call for a synthesis of both positions, where both positions would be ‘aufgehoben‘, which is a German term meaning three things: 1) both positions are overcome, 2) both positions, in that overcoming, are transformed, and 3) both positions are preserved in the new synthesis. And of course this synthesis by itself and in time will attract its own antithesis again. And so it goes on and on. And we are just at a particular stage of this development. It must be noted here that the new position, if it is ever being worked out, might be so radically different from both Theosophy and Krishnamurti that both will probably have a hard time recognizing it. And even if they recognize it, then to accept it. But, you never know how thought develops. Anyway, Krishnamurti again has something interesting to say about this possibility. In 1933 he stated:

Please do not think that in the combination of your ideas and mine, you are going to realize a unified whole.xxxv

So, he says, forget about it. “You cannot take what I say and add it to your own. You cannot mix oil and water.”

The fifth and last manner to deal with these differences is to see them as complementary, archetypal modes of spirituality. They are both legitimate ways between which one can alternate during different phases of one’s life. During one phase it might be legitimate to seek out the Masters, try to qualify for initiations and accept a gradual process. And at another time it might be legitimate to toss that all out, just go solo and aim at a complete transformation. You can switch between the two according to what feels right. A question here might be that, if you make these switches, you might lose everything you have gained in one mode. You might keep merely switching around and go nowhere.

Further lines of investigation

There are further lines of investigation to be engaged in. First of all it would be interesting to investigate how Theosophical perceptions of Krishnamurti’s metaphysical status line up with specific evaluations of his teachings. Do all those who see K as the World Teacher also agree with his teachings? And do all those who do not see K as the World Teacher also disagree with his teachings? Overall that is the case, but there are intriguing exceptions.

Secondly, one could look at Krishnamurti and everything he put into motion as the emergence of a new civilization. The structure of that civilization would be as follows: in the middle you have Krishnamurti as remembered, i.e. the enigmatic and charismatic person himself. Around that, his teachings as they are preserved in books and videos. Around that, an organizational circle of the Krishnamurti foundations and the Krishnamurti schools where you will find a first circle of social structurization. And then, in a larger circle, all the institutions and habits of society at large which can become increasingly restructured by the inspirations coming from the first three parts. I propose to name the organized spiritual aspect of this civilization Krishnamurtianity and the wider culture the Krishnamurtian Civilization. Such terminology is purely descriptive and does not entail any valuation. It is my hope that academic disciplines like religious studies, psychology, sociology and history will take notice of that because it might be a unique phenomenon to investigate, i.e. the emergence of a whole new civilization.xxxvi Of course, on the other side, other academics might say it is merely a sect and not interesting.

Another aspect which has to be further investigated–and here I am very much with the philosopher Aryel Sanat–is looking at Krishnamurti’s teachings with the analytical tools developed by the philosophical movement of phenomenology.xxxvii Certain studies have already been undertaken like comparing Krishnamurti and Edmund Husserl, the founder of that movement.xxxviii There are also some studies comparing Krishnamurti with the early works of the French existentialist Jean-Paul Sartre, who was a phenomenologist.xxxix I made a list of reasons why phenomenology, Krishnamurti and Theosophy are relevant to each other.xl

Another investigation would be, and I call this the “micro investigation of the changes of vocabulary” of Krishnamurti around the crucial period of 1925 – 1929, i.e. the period before 1925 when he was still a convinced Theosophist, then the days when everything was changing because of his own deep mystical experiences, and then after 1929 when he went solo and distanced himself from anything esoteric. What were the gradual changes in his vocabulary?

Another project would be to put the Krishnamurti narrative within a grand Theosophical narrative. Blavatsky in The Key to Theosophy, the same book that I quoted from and in the very same chapter where she talks about a coming torch-bearer of truth, made a suggestion to look for outbursts of spirituality in the west during the last quarter of every century.xli She stated that there are certain teachers showing up and certain spiritual things happening in those twenty-five years which will shape the century to come. I took her idea serious and was indeed able to develop an alternate, esoteric history of the west, including identifying some of its main cycles.xlii

Then there are some critical readings to be done of some of the major studies of Krishnamurti. Aryel Sanat’s The Inner Life of Krishnamurti is one as well as the article “Realization or Revelation” by Dutch Theosophist J.J. van der Leeuw, who puts Krishnamurti and Theosophy against each other. And a paper titled “Was K Simplistic In His Approach To The Psyche?” by Carol Brandt, which was published in the magazine The Link, which I found very interesting. She compared some of the latest research on consciousness with what Krishnamurti was saying.

Then there is K’s possible early exposure to Advaita Vedanta through one of his teachers, the Theosophist Ernest Wood. He wrote The Pinnacle of Indian Thought, which is a translation with commentaries of The Crest Jewel of Discrimination allegedly by Advaita’s founding father Shankaracharya. The lead question would be, if K picked up already early in his life some basic Advaita concepts which then worked their way into his mature philosophy.

A last item to look into is K’s friendship with Vimala Thakar, the possibly one and only person having gone through K’s proposed radical transformation of consciousness. She lived a fascinating life and was considered by the What Is Enlightenment? magazine as the “most enlightened person in the world”.xliii She wrote a small, charming autobiography about her encounter with K and some see her as a female version of K.xliv

In short, there is still lots to investigate and the above is only a small contribution to an ongoing research agenda.

Bibliography

The Theosophist 107/6 (March 1986) & The Theosophist 116/8 (May 1995). Special Krishnamurti issues.

Alcyone (Krishnamurti). 1911 (2000). At the Feet of the Masters. Wheaton, IL: Theosophical Publishing House.

Algeo, John. 1995. “Review of Krishnamurti–Love and Freedom by Peter Michel”. Quest, 8/3: 86-87.

*Anonymous Master. 1926. “A Message to the Members of the Theosophical Society from an Elder Brother”. The Theosophist 47/4 (January 1926), Supplement: 1-7.

*Anrias, David. 1932. Through the Eyes of the Masters: Meditations and Portraits. London: Routledge.

Agrawal, M. M. 1991a. Consciousness and the Integrated Being: Sartre and Krishnamurti. Shimla, India: Indian Institute of Advanced Studies.

——-. 1991b. “Nothingness and Freedom: Sartre and Krishnamurti”. Journal of Indian Council of Philosophical Research, 9/1: 45-58.

Bailey, Alice. 1955. Discipleship in the New Age, vol.2. New York: Lucis Trust.

Besant, Annie. 1912. “Freedom of Opinion in the T.S.” Letter to The Vâhan 21\8 (March 1912): 153.

——-. 1930. “To Members of the Theosophical Society”. The Theosophist, 51\6 (March 1930).

Blavatsky, H.P. 1968. H.P. Blavatsky: Collected Writings. Vol. 3. Wheaton, IL: Theosophical Publishing House.

——-. 1995 (1889). The Key to Theosophy. Pasadena, CA: Theosophical University Press.

Brandt, Carol. 2003. “Was K Simplistic In His Approach To The Psyche?” The Link, 22.

Burnier, Radha. “J. Krishnamurti”. The Theosophist, 107/6 (March 1986). See also The Theosophist, 116/8 (May 1995).

Fouéré, René. n.d. “Krishnamurti et l’Existentialisme”. In: Linsen, Robert (Ed.), Krishnamurti et la Pensée Occidentale. Brussles: Editions Être Libre.

Fuller, Jean Overton. 1986. “Krishnamurti”. Theosophical History, 1/6 (April 1986): 140-142.

——-. 1998. Cyril Scott and a Hidden School: Towards the Peeling of an Onion. Theosophical History Journal, Occasional Paper VII.

Gunturu, Vanamali. 1998. Jiddu Krishnamurti’s Gedanken auser der Phaenomenologischen Perspective Edmund Husserl’s. Ph.D. Thesis. Frankfurt: Peter Lang.

Herzberger, Hans and Radhika (Eds.). 1995. “Krishnamurti on Theosophy: A Collection of Reference Materials”. Working Paper #4. Rishi Valley Study Centre, May 1995, Revised October 1996.

*Hodson, Geoffrey. ca. 1939. Krishnamurti and the Search for Light. Sydney: St. Alban Press.

Hodson, Geoffrey. 1929. Thus Have I Heard: A Book of Spiritual and Occult Gleanings from the Teachings of the Great. Adyar, India: Theosophical Publishing House.

*Hodson, Geoffrey. 1929. “Camp-fire Gleams” in Thus Have I Heard, 101-115.

*Keidan, Bill. 2000. “What really happened to J. Krishnamurti?” Alpheus, January, 2000.

Krishnamurti, Jiddu. 1929. “The Dissolution of the Order of the Star”. International Star Bulletin, (September 1929): 28-34. Also titled “Truth is a Pathless Land”.

—–. 1977. Truth and Actuality. London: Victor Gollancz.

—–. 2014. The Collected Works of J.Krishnamurti. Vols. I – XVIII. Delhi: Motalil Banarsidass.

Landau, Rom. 1935. God is my Adventure. London: Nicholson & Watson.

Leadbeater, Charles Webster. 1925. The Lives of Alcyone. Two volumes. Adyar, India: Theosophical Publishing House.

—–. 1930. “Art Thou He That Should Come?” The Theosophist, 51/9 (June 1930): 470-479.

*Leeuw, J.J. van der. 1930. “Revelation or Realization: The Conflict in Theosophy”. Amsterdam: TS?

Love, Robert. 2010. The Great Oom: The Improbable Birth of Yoga in America. New York; Viking.

Michel, Peter. 1995. Krishnamurti: Love and Freedom. Woodside, CA: Bluestar Communications.

Prophet, Elizabeth Claire. 1975. The Chela and the Path. Malibu, CA: Summit University Press.

*——-. 1976. “An Exposé of False Teachings”. Messsage from Kuthumi. Pearls of Wisdom, 19/5: 25-30.

Quigley, Carroll. 1979 (1961). The Evolution of Civilizations: An Introduction to Historical Analysis. Indianapolis, IN: Liberty Fund,.

Ransom, Josephine. 1938. A Short History of The Theosophical Society, 1875-1937. Adyar, Madras, India: Theosophical Publishing House.

Robertson, John K. 1971. “Aquarian Occultist: The Life and Teachings of Geoffrey Hodson”. Unpublished MS.

Sanat, Aryel. 1988. “The Secret Doctrine, Krishnamurti & Transformation”. The American Theosophist, 76/5 (May 1988): 133-143.

——-. 1999. The Inner Life of Krishnamurti: Private Passion and Perennial Wisdom. Wheaton, IL: Theosophical Publishing House.

Sanderson, Stephen K. 1999. Social Transformations: A General Theory of Historical Development. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Schuller, Govert. 1997a. Krishnamurti and the World Teacher Project: Some Theosophical Perceptions. Theosophical History Journal, Occasional Paper V.

——-. 1997b. “Krishnamurti: An Esoteric View of his Teachings“. Alpheus, 1997.

——-. 1997c. “The Masters and Their Emissaries: From H.P.B. to Guru Ma and Beyond”. Alpheus, 1997, 2nd edition 1999.

——-. 2005a. “Comparison between Theosophy and Krishnamurti“. Double Column Comparison with Footnotes. Alpheus, 2005. Updated in 2019.

——-. 2005b. “The Relevance of Phenomenology for Theosophy“. Alpheus, 16 April 2005.

——-. 2006. “Centennial Efforts and Counter-Efforts of the Millennium“. Alpheus, March, 2006.

——-. 2009. “Rhythms of Spiritual Enlightenments and Counter-Enlightenments”. Diagram in Reader, 2009: 136.

Scott, Cyril [His Pupil]. 1927. The Initiate in the New World. London: Routledge.

*Scott, Cyril [His Pupil]. 1932. The Initiate in the Dark Cycle. London: Routledge.

Thakar, Vimala. 1966. On an Eternal Voyage. Hilversum, Netherlands: E.A.M. Frankena-Geraets.

——-. 2006. “Awakening to Total Revolution: Enlightenment and the World Crisis“. What Is Enlightenment? Issue 15.

Tillett, Gregory. 1982. The Elder Brother: A Biography of Charles Webster Leadbeater. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Toynbee, Arnold J. 1947. A Study of History: Abridgement of. 2 volumes. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Vedaparayana, Gandikota. 2005. Jean-Paul Sartre and Jiddu Krishnamurti on Consciousness and Freedom. Tirupati: Sri Venkateswara University.

——-. 2009. Collected Essays on J.P. Sartre and J. Krishnamurti. Tirupati: Sri Venkateswara University.

Wood, Ernest. 1967. The Pinnacle of Indian Thought. Wheaton, IL: Theosophical Publishing House.

*Article partially or integrally posted on www.alpheus.org

Larger annotated bibliography at http://www.alpheus.org/html/bibliography/k_bibliography.html1

New, categorized bibliography at

Krishnamurti Bibliography – Work in Progress

This article is based on the text of a lecture by the same title given at the Theosophical Society in America in 2004. The text is slightly expanded and references to sources have been added. Apologies for the dysfunctional endnote apparatus. I have not yet figured out how to make OpenOffice and WordPress compatible.

Endnotes

i Krishnamurti, Ojai, 24 Jan 1932.

ii Ransom, 5.

iii Blavatsky, 1995: 307.

iv Besant, 1912: 53.

v Hodson, 1929:101-115

vi Krishnamurti, 1929.

vii Schuller, 1997. All subsequent quotes from same.

viii Krishnamurti, 1977: 88.

ix Anrias, 1932: 66.

x Prophet, 1976: 29.

xi Tillett, 1982: 276.

xii Landau, 1933: 100.

xiii Herzberger, 1995: 2.

xiv Besant, 1930: 535.

xv Krishnamurti, Vol. V, 2014: 354. Third Talk, London, England, October 16, 1949.

xvi Burnier, 1986.

xvii Hodson, 1939: 9.

xviii Quoted in Robertson, 1971: 190-191.

xix Scott, 1932: 136.

xx Ibid.

xxi Leadbeater, 1925, Vol. II: 266.

xxii Leadbeater, 1925, Vol. II: 293.

xxiii Blavatsky, 1968, Vol. III: 241. Italics in original.

xxiv Anrias, 1932: 67.

xxv Krishnamurti, Vol. II, 2014: 127. First Talk, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, April 13, 1935

xxvi Ommen, Netherlands, July 29, 1931; International Star Bulletin, September 1931

xxvii Krishnamurti, Vol. I, 2014: 172. Third Talk, Adyar, India, January 1, 1934.

xxviii Prophet, 1976: 29.

xxix Krishnamurti, Vol. II, 2014: 26. “Talk to Theosophists”, Auckland, New Zealand, March 31, 1934.

xxx Krishnamurti, Vol. III, 2014: 25. Sixth Talk, Ojai , USA, May 10, 1936.

xxxi Krishnamurti, Vol. II, 2014: 225-6. Second Talk, Mexico City, Mexico, October 27, 1935.

xxxii Adyar, India, December 29, 1932. Star Bulletin, May 1933.

xxxiii H.P. Blavatsky. The Theosophist, July, 1881, p. 218

xxxiv Sanat, 1999: 137.

xxxv Krishnamurti, Vol. I, 2014: 31. First Talk, Ommen, Netherlands, July 1927, 1933.

xxxvi Very helpful will be Toynbee, 1947; Quigley, 1979; and Sanderson, 1999.

xxxvii Sanat, 1999: 144 & 246.

xxxviii See Gunturu, 1998.

xxxix See Fouéré; Agrawal 1991a & 1991b; and Vedaparayana 2005 & 2009.

xl See Schuller, 2005b.

xli Blavatsky, 1995: 306.

xlii See Schuller, 2006 & 2009.

xliii Introduction to Thakar, 2006.

xliv Thakar, 1966.

One thought on “Theosophy and Krishnamurti: Harmonies and Tensions”